Structure |

Structure

Structure is the keystone

- 4. Plantation width

- 5. Number of structural layers

- 6. Habitat potential & diversity

4. Plantation Width

100 metre wide corridor planted near Inverleigh, Victoria shelters a Lucerne paddock on a lower flood plain from drying northerly winds

100 metre wide corridor planted near Inverleigh, Victoria shelters a Lucerne paddock on a lower flood plain from drying northerly winds

You can see structure in a woodland or forest when you're out walking in the bush and enjoying its natural ambiance. Its all around you though you might not at first be aware of it

The first thing you may notice is that it's probably wide enough to make you feel quite secluded from the busy human world of traffic and people. This feeling of seclusion that we all enjoy is also very important to most wildlife and it can only be achieved if the bush is wide enough. So how wide is wide enough?

A Plantation width of 50 meters or more is the first key structural principle.

Sustainable biorich landscapes need to be at least 50 meters wide to give wildlife that sense of isolation from all things human. This isolation makes them feel safe from potential disturbance so they can get on with foraging for food, building nests and rearing their young. Scientific studies of wildlife living in remnant patches and in roadside corridors clearly demonstrate that 50 meters is necessary for a diverse mix of insects, birds and mammals to survive. Scientists go a step further and recommend that wildlife need a minimum of 10 hectares, otherwise lots of important species just can't survive.

For birds and mammals to forage they prefer the shape of a football field rather than a cricket pitch. This is because they forage outwards in increasing concentric circles. Its therefore important that narrow corridors and plantations (less than 50 meters wide) lead to a remnant patch, reserve or waterway that is wider. Creating linkages around a property is a very powerful way of supporting native wildlife while controlling insect pests that they feed on in their daily movements.

The aim is to make plantations 50 m wide and long enough or linked to other patches or corridors to provide an overall area of 10 ha. Linking adds to the dynamics of plantations and is critical to providing wildlife with adequate foraging areas. You can read how this can be done and how it works by clicking to the 'connections principle'.

The first thing you may notice is that it's probably wide enough to make you feel quite secluded from the busy human world of traffic and people. This feeling of seclusion that we all enjoy is also very important to most wildlife and it can only be achieved if the bush is wide enough. So how wide is wide enough?

A Plantation width of 50 meters or more is the first key structural principle.

Sustainable biorich landscapes need to be at least 50 meters wide to give wildlife that sense of isolation from all things human. This isolation makes them feel safe from potential disturbance so they can get on with foraging for food, building nests and rearing their young. Scientific studies of wildlife living in remnant patches and in roadside corridors clearly demonstrate that 50 meters is necessary for a diverse mix of insects, birds and mammals to survive. Scientists go a step further and recommend that wildlife need a minimum of 10 hectares, otherwise lots of important species just can't survive.

For birds and mammals to forage they prefer the shape of a football field rather than a cricket pitch. This is because they forage outwards in increasing concentric circles. Its therefore important that narrow corridors and plantations (less than 50 meters wide) lead to a remnant patch, reserve or waterway that is wider. Creating linkages around a property is a very powerful way of supporting native wildlife while controlling insect pests that they feed on in their daily movements.

The aim is to make plantations 50 m wide and long enough or linked to other patches or corridors to provide an overall area of 10 ha. Linking adds to the dynamics of plantations and is critical to providing wildlife with adequate foraging areas. You can read how this can be done and how it works by clicking to the 'connections principle'.

Wethers off shears enjoying the shelter in a 50 meter wide plantation near Rokewood, Victoria

Wethers off shears enjoying the shelter in a 50 meter wide plantation near Rokewood, Victoria

Stock haven

The other benefit 50 meters width provides is protection from extreme weather for wildlife and for stock. Imagine being cozy at home on a cold, rainy and windy day and some inconsiderate person opens all your windows and doors. You'd feel very cold and miserable until you closed them again.

50 m wide plantations are more sheltered at their core and can be used to protect stock in periods of extreme weather. Crash grazing with stock can also be a useful tool to control weeds in a plantation. This is more easily managed if there are gates at each end, so that stock can be 'walked through' over a few days. Stock will do very little damage to trees and shrubs if they are kept moving and this is the way that they naturally feed in the wild.

The other benefit 50 meters width provides is protection from extreme weather for wildlife and for stock. Imagine being cozy at home on a cold, rainy and windy day and some inconsiderate person opens all your windows and doors. You'd feel very cold and miserable until you closed them again.

50 m wide plantations are more sheltered at their core and can be used to protect stock in periods of extreme weather. Crash grazing with stock can also be a useful tool to control weeds in a plantation. This is more easily managed if there are gates at each end, so that stock can be 'walked through' over a few days. Stock will do very little damage to trees and shrubs if they are kept moving and this is the way that they naturally feed in the wild.

This plantation of Red Box, Eucalyptus polyanthemos is fully exposed to wind and weather. A shrub layer planted on the outside would make it much more protected and attractive to wildlife

This plantation of Red Box, Eucalyptus polyanthemos is fully exposed to wind and weather. A shrub layer planted on the outside would make it much more protected and attractive to wildlife

The edge effect

The penetration of extreme weather into bush areas or plantations is like opening the windows and doors in your home and is called the 'edge effect'. Good design tries to minimise the edge effect by making plantations wide enough and by planting bushy shrubs along the outer edges to keep the weather out. I'm sure you've taken shelter behind a dense shrub when a freak storm has come out of nowhere and a driving wind has pelted you with rain. In exactly the same way dense shrubs planted on the outer rows are ideal to provide weather protection for wildlife living inside a plantation.

50 meter wide biorich plantations may seem impractical

Linking a forestry plantation to a narrow remnant of wet forest adds width and area which is valued by wildlife

Linking a forestry plantation to a narrow remnant of wet forest adds width and area which is valued by wildlife

Some of you will be thinking that its not practical or even possible to incorporate 50 m wide biorich plantations into your property.

Here are some practical solutions to help narrow plantations provide better habitat for wildlife;

Here are some practical solutions to help narrow plantations provide better habitat for wildlife;

- To ease into the idea of wider plantations, start by adding some extra rows and incorporating income generating plants for firewood, timber, cut flowers, nuts, oil production, honey flora. This will make the plantation part of your farm enterprise and also means that you get to spend time in a woodland/forest environment while you're harvesting the various products. Read more on designing for profit

- Plant beside an existing roadside corridor or neighbour's plantation - 25 meters wide on each property.

- Round off the corners in paddocks that are awkward for farm machinery. This will widen existing windbreaks at every paddock corner.

- Add several rows of a perennial fodder plants like the hardy shrub Old Man Salt-bush, Atriplex nummularia, in paddocks next to existing boundary plantations. Its bushy habit will provide shelter and drought fodder for sheep and dramatically reduce the 'edge effect'. Studies show the salt bush rows also provide habit for insects, birds, small mammals and reptiles. You can achieve all this without the cost of fencing.

- Link new plantations to any remnant patches and consider planting a bushy perimeter around the patch to reduce the edge effect

Planting shrubs and understorey around mature River Red Gums near Inverleigh, Victoria

Planting shrubs and understorey around mature River Red Gums near Inverleigh, Victoria

- Include old paddock trees where possible, even if they are dead.

Old trees with hollows are called 'keystone features' on rural landscapes because they are critically important for wildlife migration and provide homes for a huge variety of fauna. Like keystones in a brick building, remove them and cracks will appear over the whole wall before it eventually collapses. In the same way, the ecosystems that depend on the old trees and the wildlife they support will collapse without them. - Paddock trees are not being replaced because of constant grazing pressure. A study in 2009 by ANU of 1,000,000ha in south eastern Australia found the old paddock trees are dying at a rate of 2%/year.

Under existing management practices millions of hectares currently supporting tens of millions of trees will be treeless within decades. - The study recommended new grazing practices like ‘High Intensity Grazing/‘Fast Rotational Grazing' that resulted in 4 x increase in natural regeneration from old trees. This involved grazing intensly for several days and resting for a few month and reducing fertliser use.

- Read more about them in The Sentinals story and under 'Habitat potential and diversity' below.

The city nature strips can provide habitat for wildlife and produce to share

The city nature strips can provide habitat for wildlife and produce to share

Living in the city planting the nature strips as well your boundaries with indigenous tussock grasses, shrubs and understorey plants will bring back many native bird species. Try adding some banksias for cut flowers to give/sell to passersby

Trees over 8 meters are usually too big for city plantings because of the size of their root systems. My rule of thumb is that roots will spread 1.5 times the height from the trunk. Therefore a 10 m tall tree will have roots 15 m from its trunk. These roots will compete with all the other plants within 15 m for soil moisture particularly in the summer months.

These tall trees will shade the garden all year round making it cooler in the summer but cold in the winter. Deciduous trees may be a better choice where more winter sunlight is desirable and are compatible with an under-planting of native shrubs and native grasses.

The roots of tall trees (both native and deciduous) often cause structural damage to buildings and pathways, another good reason to choose smaller shade trees.

The city streets would feel more like sanctuaries with a diverse mix of screening plants between the traffic and homes and wildlife will flock back to the streets and gardens.

Before planting the nature stripe, check with your local Council. They are likely to support your initiative and have some suggestions about suitable plant species that will be an asset for everyone. They may even offer you some local native plants for free.

Trees over 8 meters are usually too big for city plantings because of the size of their root systems. My rule of thumb is that roots will spread 1.5 times the height from the trunk. Therefore a 10 m tall tree will have roots 15 m from its trunk. These roots will compete with all the other plants within 15 m for soil moisture particularly in the summer months.

These tall trees will shade the garden all year round making it cooler in the summer but cold in the winter. Deciduous trees may be a better choice where more winter sunlight is desirable and are compatible with an under-planting of native shrubs and native grasses.

The roots of tall trees (both native and deciduous) often cause structural damage to buildings and pathways, another good reason to choose smaller shade trees.

The city streets would feel more like sanctuaries with a diverse mix of screening plants between the traffic and homes and wildlife will flock back to the streets and gardens.

Before planting the nature stripe, check with your local Council. They are likely to support your initiative and have some suggestions about suitable plant species that will be an asset for everyone. They may even offer you some local native plants for free.

5. Number of structural layers

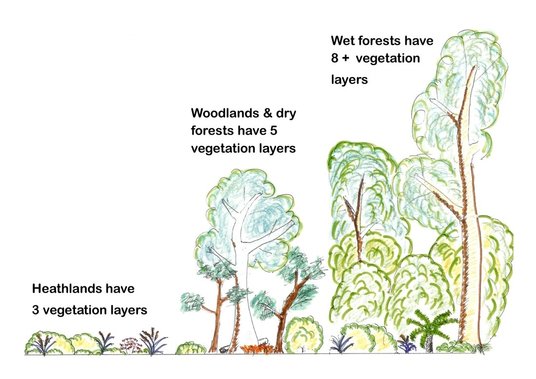

Vegetation layers in three very different ecologys. The layering provides a more diverse habitat and results in much more wildlife

Vegetation layers in three very different ecologys. The layering provides a more diverse habitat and results in much more wildlife

Structural layers are like the shelves in your pantry. You can store more food in less space and its easier to find. In nature the shelves are the vegetation layers and not only do they provide more food that is convenient to harvest, they provide shelter and screening for protection from predators as well.

Structural layering in nature occurs when a clump of small plants grows next a clump of taller plants.

This height difference can easily be seen if we stand back and imagine the bush in two dimensions rather than the normal three dimensions. The height differences you will see are infinite, from herbs, grasses and logs on the ground through every conceivable size up the the tallest trees.

Ecologists have noticed that in this infinite variation in sizes there is a pattern. For example in 'woodlands' and 'dry forests' they have observed 5 layers, in 'heathlands' there are usually 3 layers and in the 'wet forests' of the Otway Ranges

there are over 8 layers.

These structural layers also provide wildlife with shelter and protection from extreme weather as well as predators.

They also make it possible for a greater diversity of insects, birds and mammals to thrive in several ways;

Structural layering in nature occurs when a clump of small plants grows next a clump of taller plants.

This height difference can easily be seen if we stand back and imagine the bush in two dimensions rather than the normal three dimensions. The height differences you will see are infinite, from herbs, grasses and logs on the ground through every conceivable size up the the tallest trees.

Ecologists have noticed that in this infinite variation in sizes there is a pattern. For example in 'woodlands' and 'dry forests' they have observed 5 layers, in 'heathlands' there are usually 3 layers and in the 'wet forests' of the Otway Ranges

there are over 8 layers.

These structural layers also provide wildlife with shelter and protection from extreme weather as well as predators.

They also make it possible for a greater diversity of insects, birds and mammals to thrive in several ways;

- More layers = more diversity of wildlife. Different wildlife feed, nest and perch at different levels. If some layers are absent, so will the wildlife that need these layers be absent. For example The Common Bronzewing Pigeon forages on the ground for wattle seeds, perches in the safety of a shrub or small tree and builds its nest on the solid fork of a tree.

The White-striped Freetail Bat hibernates under the peeling bark of a eucalypt and hunts for insects below the canopy around the shrub layer. Without all these layers neither the Bronzewing Pigeon nor the Freetail Bat could live in the woodland.

See An Ecology Snapshot for a quick look at where & how different wildlife use the vegetation layers - More layers = less predators. Common introduced predators like the Red Fox, feral cat and wild dog like open areas with a few scattered trees where they have good line of site for hunting and self preservation. Add logs, shrubs and the taller vegetation layers and they will hunt around the fringes but they usually wont penetrate too deep into the sheltered bushy interior.

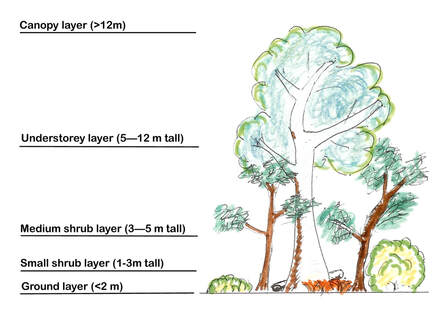

The 5 structural layers in a woodland or dry forest

The 5 structural layers in a woodland or dry forest

Dry forests and woodlands

The ground layer is where it gets messy and is what you may trip over when your walking through bushland. It's made up of leaf litter, logs, rocks, tussock grasses, native herbaceous plants, lichens and mosses. This messiness is a sign of good health.

In an area the size of a tennis court a healthy ground layer will have 10 - 20 meters of fallen logs. That is, if you put all the logs 10 cm diameter and larger end to end they would have total length of 10 - 20 meters.

This layer is critical for insects and fauna that live on the ground. For example fox predation of reptiles, small mammals and birds is reduced on roadsides with a healthy ground layer with fallen logs because they have somewhere secure to hide.

The small shrub layer (1-3 m) & medium shrub layer (3-5 m) are bushy and provides nesting sites for small birds like the Suburb Blue Wren and the Brown Antechinus, a cute carnivorous marsupial the size of a mouse.

This layer is often provided by small eucalypts, melaleucas, tea-trees, bottlebrushes, small banksias, grevilleas and hakeas, native daisy bushes, small wattles, salt bush species, as well as Wedge-leaf Hop-bush, boobialla species, Tree Violet and Hop Goodenia to list a few.

These shrub layers provide important shelter from aerial predators like the Brown Goshawk. Feral animals are also put off by dense bushy understorey particularly if some if it is prickly.

They also protect sheltering wildlife from extreme weather conditions by significantly reducing wind velocities and providing shelter from the chilly driving rains in winter months.

The understorey layer (5 - 12 m) can be bushy when it is immature and tends to become more open when it matures. This layer is often provided by the taller acacias, tall banksias, medium and young eucalypts, tall melaleucas and sheoaks. These plants offer a diverse choice of foods and materials for nest building. See Acacias - the cafes of the bush, Wattles of the Geelong Region and an article on sheoaks and cypress-pine in Trees without leaves for some more insights.There are also easy to read articles on Silver Banksia and Cherry Ballart

The ground layer is where it gets messy and is what you may trip over when your walking through bushland. It's made up of leaf litter, logs, rocks, tussock grasses, native herbaceous plants, lichens and mosses. This messiness is a sign of good health.

In an area the size of a tennis court a healthy ground layer will have 10 - 20 meters of fallen logs. That is, if you put all the logs 10 cm diameter and larger end to end they would have total length of 10 - 20 meters.

This layer is critical for insects and fauna that live on the ground. For example fox predation of reptiles, small mammals and birds is reduced on roadsides with a healthy ground layer with fallen logs because they have somewhere secure to hide.

The small shrub layer (1-3 m) & medium shrub layer (3-5 m) are bushy and provides nesting sites for small birds like the Suburb Blue Wren and the Brown Antechinus, a cute carnivorous marsupial the size of a mouse.

This layer is often provided by small eucalypts, melaleucas, tea-trees, bottlebrushes, small banksias, grevilleas and hakeas, native daisy bushes, small wattles, salt bush species, as well as Wedge-leaf Hop-bush, boobialla species, Tree Violet and Hop Goodenia to list a few.

These shrub layers provide important shelter from aerial predators like the Brown Goshawk. Feral animals are also put off by dense bushy understorey particularly if some if it is prickly.

They also protect sheltering wildlife from extreme weather conditions by significantly reducing wind velocities and providing shelter from the chilly driving rains in winter months.

The understorey layer (5 - 12 m) can be bushy when it is immature and tends to become more open when it matures. This layer is often provided by the taller acacias, tall banksias, medium and young eucalypts, tall melaleucas and sheoaks. These plants offer a diverse choice of foods and materials for nest building. See Acacias - the cafes of the bush, Wattles of the Geelong Region and an article on sheoaks and cypress-pine in Trees without leaves for some more insights.There are also easy to read articles on Silver Banksia and Cherry Ballart

Noisy Miner, Manorina menocephala, a native bird that drives out other smaller native birds to the detriment of eucalypts.

Noisy Miner, Manorina menocephala, a native bird that drives out other smaller native birds to the detriment of eucalypts.

Importantly the shrub and understorey layers will reduce or eliminate colonies of Noisy Miners, an Australian native bird that aggressively drives out other smaller birds if the woodlands and forests are too open. A Queensland study found that Noisy Miners were absent from eucalypt woodlands which had more than 20% shrub layer and 15% understorey.

When Noisy Miners and their close cousin the Bell Miners dominate a bushland, the insect pests are poorly controlled and the trees suffer. This is because the Miners have a 'sweet tooth' and maintain a high population of tiny sap sucking insects called psyllids.

The psyllids produce a dry sugary secretion that they live under called a lerp and this is the problem. The Miners 'farm' these psyllids, just eating the sugary cover. The psyllids then have to suck more sap to produce a new cover and so on. More psyllids means more food for the Miners and more stress for the trees. This process weakens the eucalypts that they live on, often causing so much stress that they start to die back and eventually die.

Small insect eating birds eat the psyllids and the lerp, giving welcome relief to the eucalypts, but they need a shrub and understorey layer to escape from aggressive the Miners that want to drive them away.

Canopy layer (above 12 m) usually consists of tall eucalypts in woodlands and dry forests. Blackwood can provide the canopy in damp areas and in wet forests with Myrtle Beech. Tall wattles, sheoaks & cypress pine provide the canopy layer in very dry desert regions.

These are the power houses of the bush providing a one stop shop for food, resources and hollows. Often growing to 15 - 30 meters in height and width, one tree can function like a small town with up to 30 hollows; many nesting sites, cracks, fissures and loose bark for insects, reptiles and micro-bats to squeeze safely into; nectar, pollen and seed in large quantities; over 300 types of resident insects; edible leaves and edible protein rich sap.

One tree can support a diverse and very large community of wildlife that in return provide many services for the canopy tree. Read 'Give me a home among the gum trees' for more insights into the partnership between eucalypts and honeyeaters

When Noisy Miners and their close cousin the Bell Miners dominate a bushland, the insect pests are poorly controlled and the trees suffer. This is because the Miners have a 'sweet tooth' and maintain a high population of tiny sap sucking insects called psyllids.

The psyllids produce a dry sugary secretion that they live under called a lerp and this is the problem. The Miners 'farm' these psyllids, just eating the sugary cover. The psyllids then have to suck more sap to produce a new cover and so on. More psyllids means more food for the Miners and more stress for the trees. This process weakens the eucalypts that they live on, often causing so much stress that they start to die back and eventually die.

Small insect eating birds eat the psyllids and the lerp, giving welcome relief to the eucalypts, but they need a shrub and understorey layer to escape from aggressive the Miners that want to drive them away.

Canopy layer (above 12 m) usually consists of tall eucalypts in woodlands and dry forests. Blackwood can provide the canopy in damp areas and in wet forests with Myrtle Beech. Tall wattles, sheoaks & cypress pine provide the canopy layer in very dry desert regions.

These are the power houses of the bush providing a one stop shop for food, resources and hollows. Often growing to 15 - 30 meters in height and width, one tree can function like a small town with up to 30 hollows; many nesting sites, cracks, fissures and loose bark for insects, reptiles and micro-bats to squeeze safely into; nectar, pollen and seed in large quantities; over 300 types of resident insects; edible leaves and edible protein rich sap.

One tree can support a diverse and very large community of wildlife that in return provide many services for the canopy tree. Read 'Give me a home among the gum trees' for more insights into the partnership between eucalypts and honeyeaters

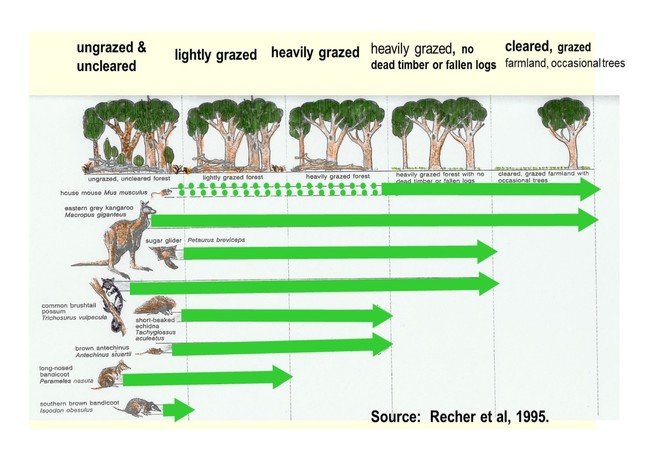

Imagine a bush scene as it was before the land was cleared and step by step remove the different layers until only an open grassy paddock is left.

What animals will each of these clearing steps evict from their habitat?

The unspoiled vegetation supports all the fauna shown (except the house mouse) because there are logs, tussocks and shrubs providing important shelter.

Bit by bit we clear away all the messy bits until we are just left with some old trees with a grassy ground layer. At this point the Eastern Grey Kangaroos are breeding up, the Brush-tail Possum and Sugar Gliders are surviving but putting a lot of browsing stress on the remaining gum trees and the introduced mice are becoming a pest.

Take out more of the big trees to allow for the larger cropping machinery and we are only left with Kangaroos & introduced field mice.

Sounds familiar doesn't it.

What animals will each of these clearing steps evict from their habitat?

The unspoiled vegetation supports all the fauna shown (except the house mouse) because there are logs, tussocks and shrubs providing important shelter.

Bit by bit we clear away all the messy bits until we are just left with some old trees with a grassy ground layer. At this point the Eastern Grey Kangaroos are breeding up, the Brush-tail Possum and Sugar Gliders are surviving but putting a lot of browsing stress on the remaining gum trees and the introduced mice are becoming a pest.

Take out more of the big trees to allow for the larger cropping machinery and we are only left with Kangaroos & introduced field mice.

Sounds familiar doesn't it.

6. Habitat potential and diversity

Poor grazing practices have resulted in the loss of these old paddock trees near Shelford, Victoria

Poor grazing practices have resulted in the loss of these old paddock trees near Shelford, Victoria

There is a clear overlap between this section and the 'Structural Layers' section above but there are some important features to consider.

This Habitat Potential and Diversity section will highlight how only old trees, either standing or fallen, can provide hollows, large cracks and fissures for insects, reptiles, amphibians, birds and mammals to squeeze into for refuge, for an overnight stay or to raise their young in relative safety.

Old trees are a sign of a mature ecology and they support an absolutely unique group of fauna that can't be quickly replaced when they're lost. Over 300 species of Australian fauna depend on hollows during part of their life cycle.

The importance of old paddock trees with hollows and on-ground habitat like logs, rocks and tussock grasses can never be over stated.

If the fauna living in hollows and on the ground were a lobby group they would passionately explain how critically important to the health of the wilderness these features are. They would be particularly passionate because their 'backs are against a wall' of ignorance and no one seems to care that these old paddock trees and the on-ground habitat is being lost at an alarming rate.

If we revisit the 2009, ANU (Australian National University) study of 1,000,000 ha in eastern Australia that found 2% of old hollow bearing paddock trees are dying each year, the immensity of this loss is hard to appreciate.

One way of putting this into perspective is to do some number crunching;

The average number of old trees growing on a hectare would be at least 5 (more likely 5 - 10 trees/ha) and each of these old trees would have at least 30 hollows of various sizes. That adds up to 150 hollows per hectare. Multiply 150 x 2% of 1,000,000 ha (the total area of the study) = 3 million hollows (homes) being lost each year. That doesn't take into account all the other services provided by mature old trees.

That's equivalent in human terms to a city the size of Melbourne being lost each year. Its even more sobering when you realise that that is only one study covering an area 1/24th the size of Victoria, Australia's second smallest state. How would these city dwellers feel if we said that if funding became available we could rebuild their homes but it would be over 100 years before they could move back in. That's how long it takes for a gum tree to mature enough to have small hollows. The big hollows can take 200 -300 years to develop. Not much consolation if you're a homeless Ringtail Possum, Pardalote, Sugar Glider or Boobook Owl.

This Habitat Potential and Diversity section will highlight how only old trees, either standing or fallen, can provide hollows, large cracks and fissures for insects, reptiles, amphibians, birds and mammals to squeeze into for refuge, for an overnight stay or to raise their young in relative safety.

Old trees are a sign of a mature ecology and they support an absolutely unique group of fauna that can't be quickly replaced when they're lost. Over 300 species of Australian fauna depend on hollows during part of their life cycle.

The importance of old paddock trees with hollows and on-ground habitat like logs, rocks and tussock grasses can never be over stated.

If the fauna living in hollows and on the ground were a lobby group they would passionately explain how critically important to the health of the wilderness these features are. They would be particularly passionate because their 'backs are against a wall' of ignorance and no one seems to care that these old paddock trees and the on-ground habitat is being lost at an alarming rate.

If we revisit the 2009, ANU (Australian National University) study of 1,000,000 ha in eastern Australia that found 2% of old hollow bearing paddock trees are dying each year, the immensity of this loss is hard to appreciate.

One way of putting this into perspective is to do some number crunching;

The average number of old trees growing on a hectare would be at least 5 (more likely 5 - 10 trees/ha) and each of these old trees would have at least 30 hollows of various sizes. That adds up to 150 hollows per hectare. Multiply 150 x 2% of 1,000,000 ha (the total area of the study) = 3 million hollows (homes) being lost each year. That doesn't take into account all the other services provided by mature old trees.

That's equivalent in human terms to a city the size of Melbourne being lost each year. Its even more sobering when you realise that that is only one study covering an area 1/24th the size of Victoria, Australia's second smallest state. How would these city dwellers feel if we said that if funding became available we could rebuild their homes but it would be over 100 years before they could move back in. That's how long it takes for a gum tree to mature enough to have small hollows. The big hollows can take 200 -300 years to develop. Not much consolation if you're a homeless Ringtail Possum, Pardalote, Sugar Glider or Boobook Owl.

A future planting site running into a dry creek bed near Inverleigh, Victoria. Cobbles and bounders have been pushed up to provide on ground habitat under mature trees at the end of the plantation

A future planting site running into a dry creek bed near Inverleigh, Victoria. Cobbles and bounders have been pushed up to provide on ground habitat under mature trees at the end of the plantation

So it follows that incorporating old trees with hollows into new plantations and placing logs on the ground will add maturity to a plantation that would otherwise take over a century to develop naturally.

Even if the old paddock trees are not included in a new plantation and are within line of sight (25 - 50 meters) nearby in a paddock, some insects, birds and mammals will benefit from this loose connection.

By planting back the understorey and shrub layer in the vicinity of the old trees, their health will improve;

Even if the old paddock trees are not included in a new plantation and are within line of sight (25 - 50 meters) nearby in a paddock, some insects, birds and mammals will benefit from this loose connection.

By planting back the understorey and shrub layer in the vicinity of the old trees, their health will improve;

- The diversity of insect, birds and microbats will restore some balance and leaf-eating insect control

- Stress caused by sheep camping under old trees, raising nutrient levels and compacting the soil will end

Placing red gum logs in a new plantation to provide fauna habitat at ground level. The huge limbs had fallen from a tree in a nearby cropping paddock.

Placing red gum logs in a new plantation to provide fauna habitat at ground level. The huge limbs had fallen from a tree in a nearby cropping paddock.

On-ground habitat is mostly absent in new plantations. The most likely elements that might be present are tussock grasses and occasionally a fallen log and it takes a lot of resources and time to add them in before planting. Occasionally an old pine or cypress plantation has been pushed over to make way for a new plantation. Its better for the ecology of a new plantation to spread these around and plant between the old logs than push them in a heap to burn. This provides an immediate richness of habitat at ground level that would normally take decades and even centuries to develop.

Short lived species like Australia's floral emblem, the Golden Wattle, Acacia pycnantha, will grow quite large in 5 - 10 years, die and fall over. Scatterings and clumps of Golden Wattle in a biorich plantation are an excellent way to quickly build the ground layer with fallen logs while providing many other benefits to the local ecology - for more on this read

Food Source Potential

Short lived species like Australia's floral emblem, the Golden Wattle, Acacia pycnantha, will grow quite large in 5 - 10 years, die and fall over. Scatterings and clumps of Golden Wattle in a biorich plantation are an excellent way to quickly build the ground layer with fallen logs while providing many other benefits to the local ecology - for more on this read

Food Source Potential

A roadside grassland near Rokewood, Victoria. Feather heads, Ptilotus macrocephalus in the foreground

A roadside grassland near Rokewood, Victoria. Feather heads, Ptilotus macrocephalus in the foreground

Grasslands.

The ground layer is where you will also find remnant grassland plants, particularly in Grassy Woodland EVC's (Ecological Vegetation Classes) where the space between the canopy trees is wider than 'dry forests' letting in my sunlight.

Healthy native grassland communities can support an extraordinary diversity of species of orchids, lilies, grasses and wildflowers.

They are;

In the Geelong district on the basalt plains the rare and endangered grassland fauna include, the Striped Legless Lizard, Delma impar; the Fat-tailed Dunnart, Sminthopsis crassicaudata; Golden Sun Moth, Synemon plana and the Growling Grass Frog, Litoria raniformis. All of these species are protected and are only found in grasslands or nearby wetlands as in the case of the Growling Grass Frog. See images below

Native grasslands have heritage values and they are also economically valuable to a farming enterprise. For example, a common grass that is found in these grasslands is Kangaroo Grass, Themeda triandra. Kangaroo Grass provides excellent late spring and summer grazing for stock and because it's a summer active grass it is a fire retardant. This is because it carries very little dry flammable straw and summer rains will keep it green.

In addition to these benefits the seed has value. One hectare of Kangaroo Grass will usually fill a wool bail with florets (the seed heads) valued at $1,000 - $2,000. Not bad for a crop that needs no cultivation, sowing or fertiliser and lives for over 100 years. Autumn burning every 5 - 10 years will keep it healthy.

The ground layer is where you will also find remnant grassland plants, particularly in Grassy Woodland EVC's (Ecological Vegetation Classes) where the space between the canopy trees is wider than 'dry forests' letting in my sunlight.

Healthy native grassland communities can support an extraordinary diversity of species of orchids, lilies, grasses and wildflowers.

They are;

- very rare and protected.

- complete ecosystems that are kept healthy by occasional burning and grazing.

- important food sources for rare insect, reptile, amphibian and mammal species.

- a delight to explore and best appreciated in spring from September to the end of November.

- a tourist attraction. Enthusiasts will travel long distances to see rare plants in flower.

- home to rare and endangered grassland plants such as the Shelford Leek orchid, Prasophyllum fosteri; Hoary Sunray, Leucochrysum albicans ssp tricolor; Hairy-tails, Ptilotus erebescens; Clover Glycine, Glycine latrobiana.

In the Geelong district on the basalt plains the rare and endangered grassland fauna include, the Striped Legless Lizard, Delma impar; the Fat-tailed Dunnart, Sminthopsis crassicaudata; Golden Sun Moth, Synemon plana and the Growling Grass Frog, Litoria raniformis. All of these species are protected and are only found in grasslands or nearby wetlands as in the case of the Growling Grass Frog. See images below

Native grasslands have heritage values and they are also economically valuable to a farming enterprise. For example, a common grass that is found in these grasslands is Kangaroo Grass, Themeda triandra. Kangaroo Grass provides excellent late spring and summer grazing for stock and because it's a summer active grass it is a fire retardant. This is because it carries very little dry flammable straw and summer rains will keep it green.

In addition to these benefits the seed has value. One hectare of Kangaroo Grass will usually fill a wool bail with florets (the seed heads) valued at $1,000 - $2,000. Not bad for a crop that needs no cultivation, sowing or fertiliser and lives for over 100 years. Autumn burning every 5 - 10 years will keep it healthy.