Recreating the Country blog |

The Melbourne Cricket Ground is considered a 'sacred place' by many Australians The Melbourne Cricket Ground is considered a 'sacred place' by many Australians A deep dive into the history of the G The year is 2016 and I’m looking through the window of the expansive lounge above the hallowed grounds of the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG or G). I’m feeling a bit awe-struck because like many Australians I associate the MCG with big events: the 1956 Olympics, the VFL/AFL grand final and extravaganza concerts like Guns N’ Roses, Ed Sheeran and recently Taylor Swift. Apparently, the crusader Billy Graham attracted the biggest crowd of 130,000 in 1959. Graham’s sermon to his many devotees segues with my view that the MCG is considered a ‘spiritual place,’ indeed a ‘sacred place’ by many Australians. This is the product of human folklore that began long before modern history, possibly over 60,000 years ago; but more about that later. Sadly, I wasn’t at the MCG to yell myself hoarse at the footy or to scream ecstatically a concert. I was there for a National Landcare conference to speak on sustainable design and conserving biodiversity. Sounds a little ‘ho-hum’ in comparison doesn’t it? For most Australians, ‘sustainable biorich revegetation’ would sound very mundane, and that thought worried me a lot as I looked through the window. Here we were at the MCG, about 400 members of an Australia wide community based network that works very hard to improve the natural environment for the good of everyone. Yet for most people this event and the admirable efforts of Landcare sit well below their radar.  It's been 161 years since a River Red Gum has been seen on the 2ha paddock called the MCG. Image: Tian Murphy It's been 161 years since a River Red Gum has been seen on the 2ha paddock called the MCG. Image: Tian Murphy How to put a Landcare event on their radar? Standing at that window, I imagined a group of Landcarers walking onto the MCG and planting a River Red Gum at its centre, about the middle of the cricket pitch. Just temporarily, as a conservation statement of course! I also imagined the nation-wide consternation and the widespread outrage of the Australian community. Front page headlines in newspapers around Australia might have read: ‘MCG defiled by Landare’ ‘Landcare desecrates the hallowed ground of the G’ ‘Landcare madness!’ Other more appropriate headlines could have been; ‘Landcare nods to the ancient history of G’ ‘Landcare did what? – now you’re all listening!’ ‘The River Red Gum returns to the MCG after 161 years' The brash, slightly absurd, very cheeky and highly illegal act of planting a tree in a 2ha paddock called the G would likely go viral around the world because it’s ridiculous, funny and surprising. I asked myself as I imagined the River Red Gum growing and spreading its branches to welcome back the thousands of different species of insect, bird, marsupial, reptile and amphibian to the Melbourne Cricket Ground. 'Is that what we need to do to get everyone’s attention?' And when we do have the world’s attention, for 30 seconds if we’re lucky, could we slip in a powerfully worded, very chilling statement about the 'train crash' of an extinction crisis affecting most of the flora and fauna in Australia. Or is that just being a party pooper?  Wood engraving of an Australian rules football match at the Richmond Paddock , Melbourne (MCG), about 1866. Note the well spaced very old eucalypts, which are likely to be River Red Gum and Manna Gum Wood engraving of an Australian rules football match at the Richmond Paddock , Melbourne (MCG), about 1866. Note the well spaced very old eucalypts, which are likely to be River Red Gum and Manna Gum Let me put this fictional, though notable, event into perspective: 1. A River Red Gum is planted in the middle of the MCG in 2016 2. At this time, the MCG had been a stadium for big events for 161 years. The original cricket ground nearby was in a flood zone, the cricketers changing rooms regularly being washed downstream 3. The MCG and surrounds was the spiritual home and a traditional gathering place for the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung for an estimated 60,000 years  A 400yo River Red Gum scar tree in Yarra Park near the MCG. Photo John Young A 400yo River Red Gum scar tree in Yarra Park near the MCG. Photo John Young 4. The wetlands and banks of the Birrarung (Yarra River) are very likely to have supported 400 year old River Red Gums, growing on nearby flood zones and on the MCG. Prominent among the other tree species were; Manna Gum, Swamp Gum, Blackwood, Lightwood, Silver Wattle, Black Wattle, Black Sheoak and Sweet Bursaria. 5. The 2ha MCG would have very likely supported about 8 very large River Red Gums scattered across its hallowed grounds. The historic spacing for old gums was 30-50m, which is about 4-10 trees/ha. 6. The first settlers described Melbourne as a ‘nobleman’s park,’ because regular cultural burning had kept it open and thinly wooded 7. The dominant grasses on the fertile volcanic soils of the MCG are likely to have been Kangaroo Grass, Weeping Grass, wallaby grasses and various tussock grasses. Intermixed with these would have been a rich and diverse list of flowering herbs and orchids cultivated for food and medicines by the Wurundjeri for thousands of years.  Marngrook football by William Blandowski. Marngrook football by William Blandowski. The MCG's unimaginably deep past The MCG has had an unimaginably deep past as a sacred place for the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people. They would have gathered there from regions far and wide across their shared language group, to be ‘welcomed to country,’ tell stories, share jokes, sing traditional songs, wow onlookers with traditional dances, make new friends and play games. A very popular game was Marngrook, the Wurundjeri football game played with a tightly tied possum skin, which is likely to have given birth to our own unique game of football. Two large teams could have played the game around the trees on the MCG, marking and kicking in an elaborate game of ‘keepings off’ that continued for hours. It seems very fitting then, that the MCG continues to be the spiritual home of Australian Rules football as well as an important meeting place for the many diverse cultures of the world that converge there and that now make up multicultural Melbourne. ...and the River Red Gums are still there! The scattered trees which were a feature of the traditional Wurundjeri football game are now gone, or are they? I like to think that they have transformed/mutated into the eight, unusually tall, goal and point posts at the ends of the oval, which coincidentally is the approximate number of River Red Gums that would have grown on the MCG 190 years ago when Melbourne was called Naarm.  Hollows in old paddock trees provide homes for countless arboreal insects, birds and mammals. Photo Gib Wettenhall. Ref: Recreating the Country. Ten key principles for designing sustainable landscapes. Click on image to discover more Hollows in old paddock trees provide homes for countless arboreal insects, birds and mammals. Photo Gib Wettenhall. Ref: Recreating the Country. Ten key principles for designing sustainable landscapes. Click on image to discover more The importance of paddock trees It’s clearly not appropriate to plant trees on the hallowed turf of the MCG, though the scary truth is that Australian wildlife is in crisis and the country desperately needs more paddock trees to be planted and the remaining ancient trees protected (and encouraged to regenerate). Paddock trees restored across our 'wide brown land' would support the migration of stranded wildlife, help our flora and fauna adapt to a warming, drying climate and buffer the damaging effects of strong winds in rural areas; yes scattered paddock trees are a very effective windbreak, unlike the the goal and point posts on the MCG.  To read more about the many benefits of paddock trees click here  To learn how to plant & restore paddock trees click here  To read about the economics of protecting and planting paddock trees click here  To buy your copy of 'Recreating the Country. Ten key principles for designing sustainable landscapes' by Stephen Murphy click here

0 Comments

Guest blogger Christina Carter  Christina Carter is the Founder and Creator of Gumnut Trails adventure guides for exploring wild Melbourne. She recognises the important role that time in nature plays in increasing happiness, health, creativity and resilience in children’s development, providing them with important memories that will stick. She believes Melbourne is bursting with amazing nature spots that are perfect for parents with children to explore. You just need to know where to look... ‘It’s also true, that the more time children spend in nature when they’re young, the more they remember and care about our environment when they grow up. Let’s face it - our planet needs all the support it can get.’ (Quote from the Gumnut Trails website) Photography Tian Murphy The book launch begins  Have you ever wondered what a pardalote, a Spotted-tailed Quoll, a Brown Snake or even a Red Fox really has to say…?  Sophie Small, Bellarine Landcare's facilitator & MC for the night Sophie Small, Bellarine Landcare's facilitator & MC for the night On Wednesday June 12th, 100 Landcare enthusiasts gathered to watch a play about wildlife and launch the second edition of Stephen Murphy’s book – ‘Recreating the Country,’ were about to find out. As the audience were taking their seats; the western wall of Tuckerberry Hill’s café was lit by inspiring drone footage of Marcus Hill vineyard’s biorich plantation – an example of the design principles of Recreating the Country in action. Amazingly, this plantation of 7000 trees was planted single-handedly by one of the owners Margot, over just three years. It is now 14 years old. Here is 1 minute of highlights of the drone footage. Enjoy the birdsong; The opening act - the wildlife play The animals finally speak Gather round and listen to the stories of the creatures living here, though the spirit speaks through them they are uneasy as they've learnt to live in fear, but today they are with friends who have come to listen and to learn….” (Opening lines from the play: The Spirit of the Bellarine) As the ancient whisperings of wind through Drooping Sheoak faded, the Spirit of the Bellarine told a story of a past time when the landscape was cared for by the Beangala clan of the Wadawurrung people.  The Spirit of the Bellarine Peninsula invited us to slow down and listen to nature's song The Spirit of the Bellarine Peninsula invited us to slow down and listen to nature's song Slowly the 11 animals emerged one by one to share their stories amongst the audience. But what did they have to say...? Each animals’ unique personalities and stories were expertly played by the drama students from the Bellarine Secondary College. The original play was written by Stephen Murphy (our resident author) to give voice to the local wildlife we all care so deeply about. Please click on the images below to enlarge and read the captions:

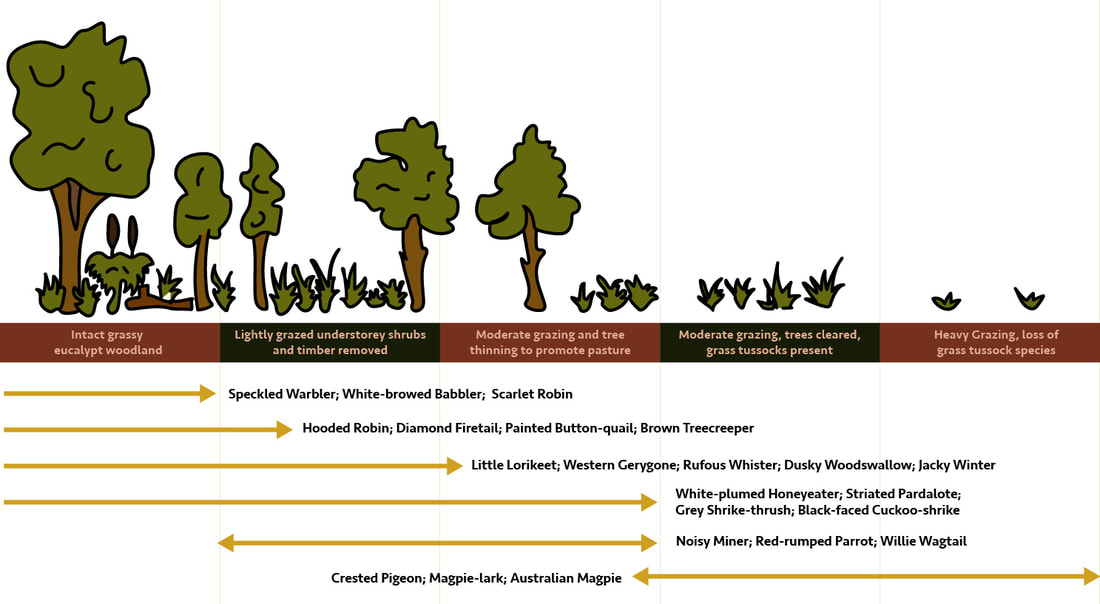

The main act - the book launch Recreating the Country. Second edition - 14 years in the making  Stephen Murphy Stephen Murphy After an introduction by Beth Ross, Stephen spoke about his passion for the environment and how the seed for his book was first sown in 2007 - when he spoke at a seminar run by Ballarat Region Treegrowers. It was Gib Wettenhall, the group’s president, an author and journalist, who suggested that Stephen’s ideas on sustainable design was a book waiting to be written - and he was 100% right! Stephen spoke about how Gib became his editor and mentor as he researched and wrote the first edition published in 2009. It was inspiring to hear about the real impact the book has had over the past 14 years. Many of the six case studies shared on the night highlighted how Stephen’s blueprint has led to thriving plantations that are self-sustaining and naturally regenerative. In contrast, we also heard about how many farm plantations sadly die out over a couple of generations due to poor design and management - often leading to more problems and expense for the landowners. Stephen is keen for people to ‘plant and connect’ with their new plantations, which he emphasised is good for their mental health as well as the natural environment. The plantation that Margot planted at the winery was highlighted as a local case study. In 14 years she established an 80m wide wildlife corridor, bringing back many local bird species, mammals and insects. Indigenous grasses are now returning naturally in what looks like a natural open woodland that has been there forever.  Thank you to Bellarine Landcare and everyone who helped to make this book launch a resounding success Thank you to Bellarine Landcare and everyone who helped to make this book launch a resounding success The Ballarat Region Treegrowers also planted a 20ha demonstration site at Lal Lal, Victoria. It now supports annual tours by Melbourne University and Deakin University students who are keen to learn about sustainable biorich design. They are excited by the prospect of biodiversity plantings providing a good income to the landowner while supporting the recovery of local wildlife. Recreating the Country is a book with generational impact If you would like to learn how to design and plant sustainable landscapes that will last for centuries - and make our land healthier and more productive. 'Recreating the Country. Ten key principles for designing sustainable landscapes' is an essential read for anyone who wants to know how to restore landscapes that will grow and evolve as nature intended. Closing credits - A big thank you to everyone involved  Beth Ross Beth Ross Thank you to Lachie Forbes, Bursaria Ecological, who filmed and arranged the drone footage, and ornithologist Glen White, for providing the morning birdsong accompanying the drone’s ‘kestrel flight.’ Thank you to Beth Ross for introducing Stephen and giving his background story, and Bernie Malone, Bellarine Landcare Group's President, for his closing remarks. Thank you to the talented drama students of Bellarine Secondary College; Alisa (Spirit of the Bellarine), Lily (Spotted Quoll & Antechinus), Pipa (Bandicoot), Macy (Sugar Glider), Rico (Spotter Pardalote & Bluetongue Skink), Isaac (Brown Snake), Roxy (Echidna & Ichneumon Wasp) and Wren (Red Fox & Platypus), for your beguiling performances. Thank you also to their supportive teacher Cassia Webster. A final big thank you to Chris and David at Tuckerberry Hill for providing their wonderful café venue and helping to make the night a success. It’s appropriate the ‘Spirit of the Bellarine Peninsula’ has the final word;  ‘The spirit of the peninsula sent out a plea to the new people who lived around, come and listen to the singing that was once such a beautiful sound, the stillness you seek can be discovered in the beauty of this place. Stop and listen to the spirit and take timeout from the rat-race, observe in nature what is needed to restore good health to this special space.’ With vegetation clearing around Australia continuing apace, Landcare has to find cost effective ways of giving wildlife links across our 'wide brown land.' Putting back paddock trees is an important part of the answer.  Paddock trees within ‘line of sight’ (25m-100m), provide vital links in the vegetation chain Paddock trees within ‘line of sight’ (25m-100m), provide vital links in the vegetation chain Paddock trees are the ‘vegetation islands’ in open farmland that provide homes for many wildlife and sleepovers for migrating species. If paddock trees are within ‘line of sight’ (25m-100m), they provide vital links in the vegetation chain, supporting the migration of many insects and bird species. Wildlife can use old trees as stepping stones, as they follow their habitual migration path for food or warmer weather. Sadly, academic studies of the life cycle of old trees throughout Australia show repeatedly that they are dying, and critically, that they aren’t being replaced by the next generation of trees. A large study in the southeast of Australia in 2009 highlighted the need to protect paddock trees. Joern Fischer and his team from ANU looked at the natural regeneration of paddock trees across one million hectares in the Upper Lachlan catchment of NSW. Within the study area, they estimated there were 3 million paddock trees (an average of 3/ha) that were typically over 140 years old. Fischer's group found that these trees are not being replaced and are dying at a rate of 2% each year. This equates to the loss of 60,000 trees/year. Put another way, if each tree averages 20 hollows of various sizes (hollows are critical habitat for over 340 species of bird, mammal, reptile and amphibian), the death of the trees will eventually lead to the loss of over 1,000,000 hollows, therefore homeless wildlife, per year within the study sample alone. This study reflects the pattern of paddock tree loss throughout Australia and it is regrettably gaining momentum each year. Planting paddock trees at regular ‘line of sight’ intervals across our rural landscapes would help re-establish critical missing vegetation connections and provide many vital benefits to wildlife, vegetation and to farming. It would act as a valuable interim measure that would help reduce the ongoing losses of biodiversity caused by the isolation of remnant vegetation patches and shelter belts. The provision of regular shade and wind protection across open landscapes would buffer rural communities from severe weather events, as well as provide significant carbon sequestration gains to the nation. Paddock trees need companion plants Improving the habitat under and around remnant paddock trees is critical. It makes an enormous difference to their health and to the diversity of wildlife that they support. Planting small indigenous shrub species & grasses under a tree’s canopy, with taller indigenous understorey trees beyond the canopy, adds in the layers of vegetation essential for the majority of wildlife. (To read more about creating vegetation layers turn to Chapter 2 of Recreating the Country Ed. 2) Note: It is important to plant taller understorey trees beyond a paddock tree's canopy. For example, the taller species of wattle, sheoak, paperbark and banksia, because they will stress the old paddock trees by competing for moisture, light and soil nutrients. The extra birds and insects attracted by these ‘companion plants’ help to control insects that defoliate the paddock trees and that also attack nearby crops and pastures. Including some nectar-producing understorey species will help to support the many insect-eating birds, lizards, mammals, parasitic wasps, flies and spiders, which are necessary to keep defoliating insects under control. ‘A healthy bird community removes between 50% & 70% of the leaf-feeding insects from patches of farm trees and so plays a valuable role in keeping those trees alive.’ (Barrett R. (2000), Birds on Farms, Birdlife Australia) To read more about paddock trees, their beauty, their values, and how to restore them, please click here  For more information about this topic and other important aspects of revegetation and landscape restoration, the new edition of, 'Recreating the Country - Ten key principles for designing sustainable landscapes,' ... will provide you with well researched and tested solutions. Click here to read more about this new book 'This is a beautiful book, which shines with the optimism and determination of the rural community, bearing witness that we can do more (individually and collectively) to recreate the country that we want.' Richard Loyn, Ecologist and adjunct professor, La Trobe University |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed