Recreating the Country blog |

This is an abridged extract from chapter 8 of my recently published book 'Recreating the Country. Ten key principles for the design of sustainable landscapes.' Ch. 8. 'Restoring natural landscapes,' takes a practical look at the different revegetation methods and reviews rewilding initiatives in Australia and worldwide. (Some of the original text and images from the book have been changed for this article). To read more about Recreating the Country, please click here  Yellow Gum, Eucalyptus leucoxylon, naturally regenerating along a roadside near Bannockburn, Victoria Yellow Gum, Eucalyptus leucoxylon, naturally regenerating along a roadside near Bannockburn, Victoria Rewilding in Australia Rewilding and natural regeneration both aim to restore local ecologies using nature-driven processes. In natural regeneration, creating the right conditions for plants to spread from roadsides and reserves is the priority. It is then hoped that wildlife will return when the plants grow and their natural habitat is re-established – ‘plant it and they will come.’ Rewilding emphasises returning animals, native to an area, in the hope that their digging, grazing and browsing will stimulate the native plants to re-emerge. Therefore rewilding has similar aims to natural regeneration, although it brings an awareness of the vital roles that wildlife play in a recovering ecology.  Cat and fox proof fencing at Tiverton Farm, Dundonald, on the Victorian Volcanic plains. This fence cost $50/m to install in 2018 Cat and fox proof fencing at Tiverton Farm, Dundonald, on the Victorian Volcanic plains. This fence cost $50/m to install in 2018 A critical first step in rewilding (& natural regeneration) is removing introduced grazing animals like sheep, cattle, horses, pigs and rabbits, as well as changing farming practices that prevent native plants from re-establishing. With rewilding in Australia, all feral predators like foxes and cats need to be excluded, so the small native grazing and digging animals can survive and support natural recovery processes. Tiverton Farm near Dundonald, Victoria, has approx. 1,000ha of predator free fencing and is home to a wild population of threatened Eastern Barred Bandicoots, released in October 2020. Eastern Quolls are soon to be released which will be the first time they will be seen in the region for over 70 years. ‘Rewilding is giving nature the space and time – critically – to dictate its own ecological trajectorie. (Nogrady, 2023) In Australia, rewilding requires more active management, because unlike the UK, Europe and USA, our ecologies have been significantly influenced by humans for more than 60,000 years. Across and throughout the continent, First Australians used sophisticated burning and soil disturbance strategies over millennia, which shaped the type and location of native vegetation and the wildlife it supported. ‘Australia’s landscapes are as much cultural as natural. People were everywhere, affecting everything, across the length and breadth of the continent over an unimaginable timescale.' Wettenhall, 2018  Weed management by Indigenous Rangers at the Tarlka Matuwa Piarku Aboriginal Corporation's reserve. Photo, Tarilka Matuwa Piarku website. Weed management by Indigenous Rangers at the Tarlka Matuwa Piarku Aboriginal Corporation's reserve. Photo, Tarilka Matuwa Piarku website. Today, much of the rewilding happening across Australia occurs under the watchful eye of Indigenous rangers. In one instance, in the northern desert regions, they are working across a vast Native Title protected area of 570,000ha, which is managed by the Tarlka Matuwa Piarku Aboriginal Corporation. Through burning and feral animal control, native wildlife and the supporting vegetation is recovering. Rewilding is also happening in fenced-off areas across Australia, where the exclusion of feral predators has allowed the reintroduction of endangered wildlife populations. The most extensive fenced sanctuaries are owned by the non-profit environment organisation, the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC), which is currently managing over 30 sites across 12.9 million hectares, some in partnership with Indigenous owners and others, as a partner with the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. A global leader in science-informed, breeding and conservation of Australia’s endangered wildlife, the AWC employs over 80 ecologists and delivers the nation’s largest biodiversity monitoring program. In Victoria, the Odonata Foundation manages six sanctuaries, including the state’s largest fenced sanctuary at Mt Rothwell, near the You Yangs, Geelong, which has successfully bred extremely rare Eastern Barred Bandicoots and Southern Brush Tail Rock Wallabies. Of particular interest are the small foraging and digging marsupials like bandicoots, bilbies, bettongs and potoroos. These animals play an essential role in our wild landscapes by disturbing the soil. This both stimulates native seed germination and spreads symbiotic fungi spores. These fungi are the indispensable partners needed by most Australian plants. Regrettably, these ‘bite-sized’ marsupials are prey for cats and foxes, though importantly they are not the usual prey of the Dingo, which prefers larger herbivores. To be entertained while you understand more about the importance of these small marsupials, click here  Dingo reintroduction trials in National Parks are long overdue. Dingo reintroduction trials in National Parks are long overdue. Apex predators and removing feral animals Dingoes have historically played a vital role in Australian ecosystems by keeping kangaroos and emus populations under control. They can also target feral goats, reducing their destructive impact on native vegetation. By controlling the numbers of herbivores, Dingoes can engineer the recovery of native plants and in the dryer parts of Australia, their effect on plant life may even affect the height and shape of sand dunes. Dingoes also limit the effect of feral cats and foxes, either by eating them or forcing them to move out of an area. ‘Dingoes can reduce the abundance of introduced foxes and feral cats. These two feral predators exert far more destructive tolls on native wildlife than dingoes do. Dingoes can also reduce grazing pressure from overabundant kangaroos and feral goats.’ Trail & Woinarski 2017. Boot camp for bettongs In the Sturt National Park, NSW, ecologist Rebecca West is part of a team that has been training Burrowing Bettongs to avoid feral predators, and they’re getting results. Their most effective training method they refer to as ‘boot camp for bettongs.’ It sounds brutal to release a few feral cats into a 26 square kilometre fenced enclosure where the bettongs are living, but they soon learn to avoid the cats. They are initially naïve about the danger, until they witness a bettong being killed and eaten. They quickly learn that cats are dangerous and that it’s smart to keep a safe distance. There is still a lot more to learn about designing the best boot camp for bettongs, but the initial trials are very encouraging.  The Longnosed Potoroos, Potorous tridactylus, were critical landscape engineers in Australia The Longnosed Potoroos, Potorous tridactylus, were critical landscape engineers in Australia In Victoria's Otway Plains the scene has been set for rewilding the Longnosed Potoroo. The East Otway Landcare group, ecologists and First Australians have been funded to trap and bate feral cats, foxes and pigs. With the removal of these pest species, native vegetation is regenerating, local birds are returning and the potoroos are being released back into the much less hostile bush environment. Another ambitious project is Aussie Ark, which was established in 2011 to save the Tasmanian Devil from extinction. More recently, the role of the organisation has expanded and now has a vision of creating a long term future for all threatened Australian species. They have a broader definition of rewilding: ‘The planned reintroduction of a plant or animal species, especially a keystone species or an apex predator into a habitat from which it has disappeared, in an effort to increase biodiversity and restore the health of an ecosystem.’ Aussie Ark, 2011  An Eastern Bettong, Bettongia gaimardi, at Mt. Rothwell Sanctuary. Photo Mt Rothwell gallery. An Eastern Bettong, Bettongia gaimardi, at Mt. Rothwell Sanctuary. Photo Mt Rothwell gallery. Rewilding in Australia will always need active human involvement as a result of the First Australians deep history of landscape management. Restoring habitat for small marsupials and being more tolerant of our top-order predator, the Dingo, will likely improve our ‘extinction balance’ and tilt it back toward pre-colonial times when natural processes supported the maintenance of healthy and resilient natural ecosystems.

2 Comments

From 'Two Worlds Colliding,' Csillag & Wainwright From 'Two Worlds Colliding,' Csillag & Wainwright In 1980, Michael Hutchence of INXS sang the haunting lyric ‘Two worlds collided,’ in the song ‘Never Tear Us Apart.’ If you're over 45 you can probably hear his words because ‘you were there.’ It seems that more than two worlds are colliding right now and Landcare’s ideals are right in the middle.  The Regent Honeyeater, Xanthomyza phrygia, once numerous along the east coast, now number only 300 birds. Photo Tim Van Leeuwen The Regent Honeyeater, Xanthomyza phrygia, once numerous along the east coast, now number only 300 birds. Photo Tim Van Leeuwen Conservation and commerce The world of commerce has been collided head-on with the world of conservation since Australia was first settled/invaded 250 years ago. Bearing witness to this is our extraordinary loss of native flora and fauna, that appears to have been accepted as an unavoidable cost of the ‘healthy’ economic growth of a new nation. PhD candidate Michelle Ward from Queensland University reminds us that we presently have 72 species of birds facing extinction. These include the Kangaroo Island Glossy Black Cockatoo, the Regent Honeyeater, and the Night Parrot which sadly has been reduced to only 150 birds. Hopefully, we can prevent the names of these species from being added to the 29 birds known to have been lost since 1788. It seems in the last two decades, governments at all levels have played down the urgency to protect our iconic plants and animals. The EPBC Act of 1999, Australia's main environmental law, has a woeful record of protecting our flora and fauna. As a conservationist, I’m hopeful that Labor’s new environment protection laws will have sharp enough teeth to prevent any further extinctions, as has been promised by the Minister for the Environment, Tanya Plibersek. At a state level, the Victorian Auditor General's Office produced a scathing report in October 2021 called ‘Protecting Victoria’s Biodiversity.’ It found that; ‘DELWP’s cost-benefit approach can also miss endangered threatened species at extreme risk of extinction. Further, DELWP continues to make limited use of available legislative tools to protect threatened species.’ Young Australians do have fair cause to criticise the seeming half-hearted efforts of older generations to protect our wildlife heritage. Please note: DWELP, The Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, is now DEECA, The Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action. Hopefully this flags a change in focus.  Traditional Owner burning in Cape York. Photo Dale Smithyman Traditional Owner burning in Cape York. Photo Dale Smithyman Contemporary and Traditional The world of Traditional Owner land management practice has collided with the world of contemporary land management in our parks and reserves. They were poles apart until the Black Summer bushfires of 2019. Then everyone began remembering that wildfires were rare in this country before the first fleet arrived in 1788. With 75% of remnant vegetation sitting on private land, this collision of traditional and contemporary management practices has unearthed both an opportunity and a responsibility for all Australians. It’s time that we acknowledge that we have amongst us representatives of an ancient culture that successfully preserved our plants and animals for millennia. We could benefit immeasurably from adopting many of their traditional management practices and their traditional philosophies of animism and inclusive conservation. This is an urgent matter, because most of the remnant patches of native bush that support endangered wildlife are isolated and degraded. They no longer provide the complexity of habitat and the critical connections that wildlife need. The day-to-day management of private and public reserves needs to change to reflect the practices and knowledge gained over thousands of years by Traditional Owners.  Harvesting Blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon) seed is easy safe work. It's currently valued at over $300/kg Harvesting Blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon) seed is easy safe work. It's currently valued at over $300/kg The need to make a connection Another aspect of this rural collision of worlds is landscape design and how we think about new plantations. For most of the history of revegetation on farms, plantations are seen as a backdrop to essential farm income-generating activities. There is an unspoken philosophy of plant and forget, with plantations being seen as little more than beneficial add-ons to boundary fences. Rarely do landowners spend much time in their plantations unless there is a problem to fix. Plantations on farms have the potential to be much more than windbreaks and shelter belts. They could protect biodiversity as well as be a dynamic source of food, medicines, timber products, cut flowers, seeds, essential oils and honey, just to name just a few potential harvests. First Australians managed their lands to provide their food and medicines. They knew their country intimately, they knew when and where to look for the resources they needed, they knew how to maintain them in good condition for future years and they knew how to keep their country safe from damaging wild-fires. They protected the natural resources because their future health and wellbeing depended on high levels of conservation. I can imagine a future Australia, where landowners follow this example and connect with plantations both practically and emotionally. They will harvest the products they need to feed their families, provide materials for the farm, and to generate an income. They will also enjoy the ambiance of the wild environment they have created and played a part in restoring. They will witness the return of plants, animals, and insects that help to maintain an ecological balance on the farm. They will live in much safer rural communities where fire is less of a summer threat.  A deeper connection with the plants and animals in a diverse natural landscape will help support human mental health A deeper connection with the plants and animals in a diverse natural landscape will help support human mental health Plantations of the future These future plantations will need to be wider and may occupy as much as 30% of rural properties. They will be frequently visited for harvesting and maintenance, as well as for leisure. The benefits to human mental health through a closer connection with nature are well documented. Wider plantations are also better suited to the spiral foraging patterns of wildlife. The more protected shelter that they provide is critical to the survival of many iconic Australian animals facing extinction. This prospect offers a win-win, where we provide for our own needs and ensure the recovery of the flora and fauna that sustain our human lifestyles. A deeper connection with plants and animals in a diverse natural landscape will help support human health and provide Australian wildlife with a guaranteed future. We would become observers of the diverse evolving ecologies in our backyards, as more than two worlds collide. In the words of American philosopher Aldo Leopold; ‘When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.’ How do we replant and restore the complex and interactive natural landscapes that wildlife need? Advertising alert!  'Recreating the Country - Ten key principles for designing sustainable landscapes,' first published in 2009, has been expanded and updated. The new edition provides easy-to-read practical guidelines for restoring natural landscapes. The book is built on over 35 years of practical experience, observation and careful research. Read more here What do experts in ecology say about the new book? Andrew Bennett. Emeritus Professor in Ecology, La Trobe University

‘Writing with passion, commitment and insight, Stephen Murphy emphasises the need to mimic nature and that working with nature requires a long-term perspective. It’s an important reminder that the actions we take today will shape the country that future generations will inherit.’ Geraint Richards. Head Forester for King Charles III ‘The sustainable biorich model is a way of breaking down the fence between farmers and foresters.’ Richard Loyn, Ecologist and adjunct professor, La Trobe University 'This is a beautiful book, which shines with the optimism and determination of the rural community, bearing witness that we can do more (individually and collectively) to recreate the country that we want.' Producing seed for native grassland restoration in a containerised Seed Production Area by John Delpratt  Guest blogger John Delpratt is an Honorary Fellow with the University of Melbourne and was a lecturer in plant production and seed technology at the University’s Burnley campus for 25 years. John has worked on native grassland conservation with an initial focus on cultivation and seed production systems for grassland forbs. With Dr Paul Gibson-Roy he has played a key role in the reconstruction of diverse native grassland communities by direct sowing grassland seed grown by volunteers in seed production areas around Victoria. John has generously offered to share with us his depth of knowledge on how large volumes of native grassland seed is produced and harvested for these impressive restoration projects.  A restored indigenous grassland, Glenelg H’way, Wickliffe. A restored indigenous grassland, Glenelg H’way, Wickliffe. A reliable source of seed A reliable source of good quality and genetically appropriate seed is an important first requirement for restoring our wonderful and diverse temperate native grasslands and grassy understorey plant communities (Images 1, 2 & 3 below). With several hundred species of grasses, grass-like species (e.g. Lomandra species), colourful forbs and small shrubs comprising natural temperate grassy communities, and only a few species available commercially as seed, the grassland restorationist is left with three choices:

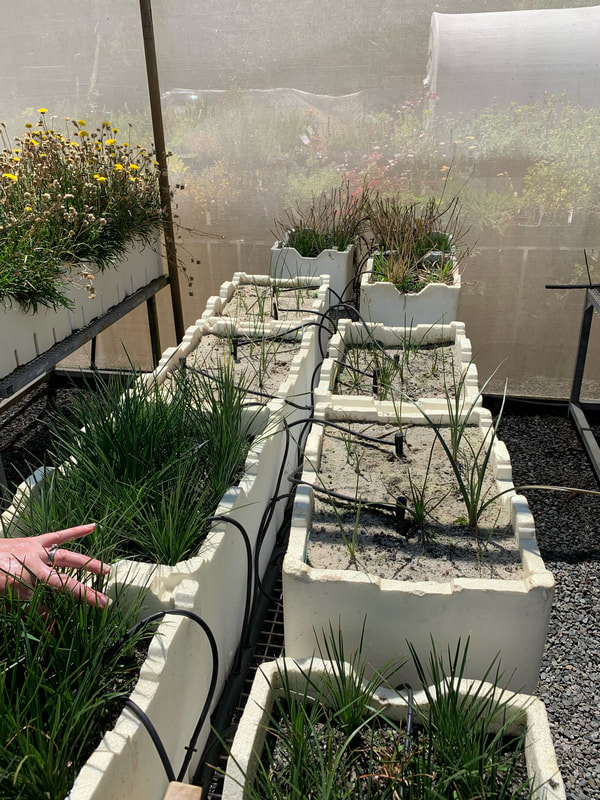

Collecting from local remnants requires careful adherence to permit conditions and a sound knowledge of the target species. Many remnants support an impressive range of look-alike introduced species. Also, good seasonal conditions and a number of site visits will be needed to capture the quantity of seed and diversity of species needed to build a functional and satisfying grassland. This leaves the third option; grow your own – the topic of this article and possibly the most fun! Please click on the images below to enlarge and read the caption Developing a seed production area (SPA) Purpose To grow your own seed as a cost-effective (but labour-intensive!) way to acquire sufficient quantities of good quality seed from a diverse range of species. Initial seed sources As already mentioned, many native grassland species are not readily available through commercial sources. Depending on your objectives and resources, you may be able to collect small, representative samples of target species under permit from local remnants. To grow the required transplants to start a SPA requires very little seed in most cases. To capture appropriate genetic diversity, small samples of seed should be harvested from numerous plants. For longer-flowering species, two or more harvests throughout the season should increase genetic diversity in your production crops. In recent years, geneticists have recommended that for widespread species, collecting from several populations is preferrable to growing from only one source. It can be difficult to discover the full history of purchased transplants. You can manage this by collecting your own seed. However, if good quality, locally-sourced tube stock is available it may be better to proceed with your SPA plan, rather than be distracted by the detail. Grow or purchase many (say 50 or more) small plants per species in preference to a few larger plants. In cultivation, most native grasses and forbs will grow at high densities and produce seed in their first year. Deciding to produce ‘climate ready’ seed can add an interesting layer of complexity. This usually involves sourcing a percentage of your seed (or transplants) from populations some distance from where you plan to restore grassland. For south-eastern Australia, this usually means sourcing some of your planting from warmer and dryer locations.  Image 4. A SPA operated by the Woorndoo Chatsworth Landcare Group to produce seed for their direct-sown native grassland restoration projects. Plants are grown in polystyrene boxes and irrigated with two microsprays per box. Image 4. A SPA operated by the Woorndoo Chatsworth Landcare Group to produce seed for their direct-sown native grassland restoration projects. Plants are grown in polystyrene boxes and irrigated with two microsprays per box. How much space do you need? The design, size and species diversity of your SPA will depend on its purpose, and the scale of your planned works. A couple of initial considerations are discussed below;

2. Are you planning to grow your seed production crops in field beds or in containers? If you are aiming to grow large quantities of native grasses, field beds may be the most affordable option. However, most field sites have a seedbank of competitive species that will quickly become contaminants in your harvested seed. Therefore, field crops require special expertise and commitment that are beyond the scope of this article, which will focus on above-ground, containerised seed production areas (SPAs).  Image 5. Burnley SPA, the production area for many of the forbs direct-sown at Gatehouse St. (image above right). Image 5. Burnley SPA, the production area for many of the forbs direct-sown at Gatehouse St. (image above right). Building and managing a containerised SPA One of the great advantages of a containerised SPA is that it can be established anywhere you have access to a bit of space, water, adequate sunlight and enough enthusiastic labour. If planning to establish a large area of grassy vegetation, the dominant grass species will usually be sourced from a commercial grower or from local field harvesting. Therefore, although an above-ground SPA can be built at any scale, they usually focus on species that add diversity and colour to an otherwise grass-dominated plant community. When designing a SPA, I strongly recommend that the plants be grown at around waist height. Although benches or other forms of support for your containers will add to the initial investment, ease of access to the crop will pay huge dividends in increased ease of maintenance operations and volunteer/staff comfort and enthusiasm (Images 4 & 5). Growing medium Any weed-free container medium that supports healthy plant growth (commercial or home-made) can be used. Long-term, controlled-release fertilisers will simplify the plants’ nutritional requirements. Re-apply annually. In grassland species, I’ve seldom seen adverse responses to phosphorus from standard N:P:K fertilisers (with Brunonia australis a possible exception). But if in doubt, use a low-phosphorus ‘natives’ product. Containers For relatively small-scale SPAs, polystyrene vegetable boxes are a light-weight, relatively durable container. We line the base of these boxes with a layer of geofabric to reduce the rate of drainage of irrigation water and to retain moisture below the growing medium. They can often be sourced for free but consistent dimensions can aid management. New boxes can be bought for a relatively small outlay. With minimal handling, the boxes can last for at least 5 years, although over time they become increasingly brittle and shed fine dust as they degrade. A single polystyrene vegetable box, filled with moist organic growing medium and plants, can be carried by one person (although, given the state of my ageing back, sharing the load may be better advice). If you wish to avoid polystyrene, the choice of container is limited only by the practicalities of your site, your construction skills, your budget and your imagination. The basic requirements are that the container can hold an adequate depth of growing medium (say, at least 200 mm), drains well and can be filled, planted, irrigated, maintained, harvested, emptied and re-planted or disposed of conveniently. Irrigation As a general rule, irrigation should be applied at the base of the plants (or below the plants if using a wicking bed or hydroponic-style irrigation system) to avoid constant wetting of flowers and developing seed (see Image 4). Some species are able to produce good quantities of seed under overhead irrigation (e.g. lilies). However, pollination, fertilisation and seed maturation in the dense heads of daisies and a number of other species can be inhibited if regularly saturated. Some form of drip or micro-spray irrigation delivers water directly to the growing medium surface. In a standard polystyrene vegetable box, this can be achieved with two outlets per box. Programable controllers allow for flexibility in the frequency and duration of irrigation as species and seasonal requirements vary. If growing in easily-transportable containers or where a dual system of overhead and drip irrigation is feasible, a further option is to grow under overhead irrigation for most of the year and move to drip irrigation from flowering through to seed harvest. Irrigation extends the reproductive period for many species and may allow for a second harvest period after an autumn flowering. However, some tuberous species may benefit from reduced irrigation during their dormant period in summer. Images below of the SPA at Burnley campus provided by Fiona Love from her recent visit. Click on the images to enlarge the 'weeping' drippers used to water plants.  Image 6. The stoloniferous Prickfoot (Eryngium vesiculosum) is one of several species grown in large tubs at WCLG’s Chatsworth SPA. This allows for both seed production and the harvesting of vegetative pieces for supplementary tube stock production or direct planting into field sites. Image 6. The stoloniferous Prickfoot (Eryngium vesiculosum) is one of several species grown in large tubs at WCLG’s Chatsworth SPA. This allows for both seed production and the harvesting of vegetative pieces for supplementary tube stock production or direct planting into field sites. Planting Planting tube stock to establish your SPA means that you can control the number and density of productive plants. Most herbaceous grassland plants can be grown to maturity at high densities. While greater numbers increase the cost of planting stock, they reduce the number of containers needed to grow the desired population of a given species. Also, it ensures you are harvesting from many small plants, rather than fewer larger plants. This strategy potentially increases the genetic diversity of your harvested seed and reduces the risk that most of your seed is harvested from fewer large plants that happen to be suited to your cultivation system. When growing in a standard polystyrene vegetable box, I usually plant from 11 to 16 plants per box (+/- 5 cm between plants). However, planting density can vary with the requirements of the species and the size of the planting stock. These same planting densities can be applied to other containers. Plants that expand by rhizomes or stolons (e.g Goodenia pinnatifida; Eryngium vesiculosum; Glycine latrobeana) are better suited to containers with a larger surface area such as raised garden beds, or similar. An added advantage is that such crops can be used for both seed production and for vegetative off-sets, cuttings or plugs. These can be used for additional tube stock propagation for supplementary plantings (Image 6 above).  To give easier access for harvest, species that produce long stems (e.g. Kennedia prostrata; Convolvulus angustissimus; Glycine clandestina) are best grown either up a trellis or where they can trail downwards. Image 7 at right is from the Burnley SPA. The trellis allows for the upward growth of Glycine clandestina. The Kennedia prostrata can spill over its boxes towards the ground. Both arrangements allow for more productive plants and easier access to the numerous seed pods.  Image 8. Murnong; Yam Daisy (Microseris walteri) in individual containers being packed into a modified box system. Once installed, the tubes were covered with additional growing medium. Irrigation water moistens the geofabric and growing medium, ensuring each plant has access to sufficient water. After a season or more of seed production, the tube stock should be available for sale or field planting. Image 8. Murnong; Yam Daisy (Microseris walteri) in individual containers being packed into a modified box system. Once installed, the tubes were covered with additional growing medium. Irrigation water moistens the geofabric and growing medium, ensuring each plant has access to sufficient water. After a season or more of seed production, the tube stock should be available for sale or field planting. Another modification I have been trying with some success is to leave the SPA plants in a container and pack them into a box that has geofabric and a layer (say 2cm) of growing medium in its base. The bottom of each container rests on the moist growing medium allowing the plant access to irrigation water, firstly by capillary action and later as its roots expand out of the container drainage holes (Image 8 below). The plan is to use the plants for seed production for one or more seasons and still have them available for planting at a later time. Early indications are that this method is best suited to relatively open-growing species. The format allows for much higher densities because each plant has access to its own water and nutrients without too much below-ground competition from its neighbours. This could prove to be a good way to grow some tuberous species such as Murnong (Microseris walteri), Milk Maids (Burchardia umbellata) and Early Nancy (Wurmbea dioica), which may establish better in the field when planted as older, more advanced stock, while harvesting seed in the meantime. However, densely-growing plants (e.g. Linum marginale, Leptorhynchos squamatus and many others) tend to experience too much above-ground competition at these higher densities, leading to plant decline within the box.  The beautiful Bulbine Lily The beautiful Bulbine Lily Harvesting Harvesting seed from small SPAs is usually done by hand or by using a small vacuum harvester. To capture most of the harvestable seed requires visiting the SPA every one to three days during peak production. However, some species can be harvested by cutting seed-bearing stems and allowing them to mature off the plant. Depending on the species, this means sacrificing some of the potential harvest but it requires much less labour. Bulbine Lily (Bulbine bulbosa) is a good example of a species whose stem can be harvested when the first two or three fruit are splitting. When the cut stems are kept intact in a dry environment, most already-formed fruits will mature their seeds over a few weeks. Of course, a level of experience is required to judge when best to harvest to limit the loss of mature seed that has already fallen while not sacrificing too much that fails to mature off the plant. ‘Optimum harvest time’ has been the subject of intense study for many agricultural and horticultural crops but has not been documented for most of our grassland species.  Kangaroo Grass, Themeda triandra, cleaned (in zip-lock bag) for sowing into tubes. KG florets and stems are visible in the black plastic tub Kangaroo Grass, Themeda triandra, cleaned (in zip-lock bag) for sowing into tubes. KG florets and stems are visible in the black plastic tub Seed processing and storage When SPA seed of herbaceous grassland species is being produced for local, more-or-less immediate use for tube stock production or direct sowing, very little processing should be required. For most species, viable seed will be harvested along with a considerable volume of leaf and floral material. For direct sowing, we check the seed lot to ensure it contains filled seed, then simply add the harvested seed and trash to our diverse seed mixes. For other applications, such as tube stock propagation, more effort can be applied to processing the harvest towards purer seed lots, usually using a combination of graded sieves and, possibly, more sophisticated gravity and air separation equipment if it is available. For short term storage (e.g. one to three years, some species for much longer), well-dried seed of most species can be stored at room temperature or in a +/- 4oC cool room without a significant loss in field germination potential. Longer term seed storage is a large topic that is well-documented in seed technology literature. Conclusion

While we work towards and await the development of a viable, regionally-based seed industry producing a comprehensive suite of native grass and grassland forb seed, restoration projects large and small will continue to rely on relatively small-scale seed production for diversity in their sowings. As well as fostering and enabling local restoration projects, well-managed SPAs are a wonderful opportunity for productive and highly satisfying volunteer involvement and, as demand grows, viable regional enterprises. The more SPAs there are, the more our species knowledge and innovative production systems will develop and be shared. And, as mentioned at the start of this article, growing seed can be a lot of fun. |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed