Recreating the Country blog |

|

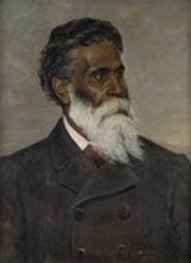

Indigenous Australians deserve much more from Landcare. Two experiences at the Landcare conference left me feeling very disappointed. An excursion out to Coranderrk settlement which is owned by the Wurundjeri Council on the Wednesday and a conversation with an indigenous elder from Geelong on the Thursday, left me thinking that we still treat the indigenous community with disregard. We did in the 1830’s and we continue to do it in 2016. I thought the National Landcare Conference would set an example for the Australian community but I was sadly mistaken.  William Barak William Barak Part 1. The story of William Barak and Coranderrk is a story of the great courage and resilience of the first Australians and it is also a story of the pathetic bloody mindedness of the first white settlers. John Batman’s fiasco of a treaty in 1835 with eight aboriginal elders on the banks of the Merri Creek lead to 360,000 hectares of land being exchanged for blankets, beads, knives and mirrors. The repercussions of this misunderstanding, the indigenous elders were offering a permit to enter their land not the sale of their heritage, resulted in the Kulin peoples being forced from their traditional grounds by farmers and their very rapid decline which was hastened by starvation and disease. Out of this monumental disaster for the indigenous peoples of the Melbourne region, a black statesman and visionary emerged, William Barak. Like Moses leading the Israelites, Barak, his uncle Billibellary and cousin Simon Wonga hoped to save his people and find them some land that they could call their own and settle-on in peace. The search for their own land started in 1843 when Barak’s uncle Billibellary approached the Aboriginal Protector, explaining that dispossession and rapid change had left his people with a sense of having no future. Billibellary’s proposal was that the government give them a block of land in their country on the Yarra so they could live and plant crops like white men. It was not until 1863 that the dream was realised and Coranderrk, a 930 hectare block, was set aside at the confluence of Badgers Creek and the Yarra River in Healesville, 60 Km east of Melbourne Soon after Coranderrk was gazetted, Barak and his cousin lead 40 men, women and children on the long walk to reach their new home. Their friend Pastor John Green, who was appointed to manage the reserve lived with them. He became their adviser and together they built a thriving village that included a school, dairy, church, bakery, butchery, hop kilns and orphan dormitories. The farm was so successful that three years later the government doubled the size of the reserve. Its population was now over 150 people. The injustice begins again as two attempts are made by parliament in 1874 & 1881 to dispossess Barak and his people of their land which was 'deemed too good for aborigines' but each time through diplomacy and campaigning, the inevitable was postponed. In that period Barak and supporters made three protest walks to parliament in Melbourne to put their case. In a press interview Barak famously said, "Me no leave it. Yarra, my country. There's no mountains for me on the Murray." In these later years the people at Coranderrk were living in poverty, because the Government was taking all their profits, leaving them to starve and freeze in the winters because they could not afford warm clothes and blankets for women and children. Barak died in 1903 and in 1923 Coranderrk was divided up for soldier settlers from the First World War, leaving only 97 hectares for the 9 indigenous people who refused to be moved off their traditional lands to the Lake Tyers Mission. I can’t help but wonder how Australia’s history might have read if Barak and his people had been rewarded for their extraordinary tenacity and compliance. After all it was their land that was taken in the first place and the parliament wouldn’t even give them back 1000 hectares. In 2016 a small group of indigenous people who are descended from the founders of Coranderrk are now restoring its health with substantial corridor plantings using whole farm planning principles. For more information on Coranderrk visit http://coranderrk.com/wordpress/?page_id=839 Part 2. Fast forward to September 2016 and a crowded foyer at the very grand Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre. I was standing alone trying to decide which one of the four themes of presentations I would choose for the afternoon, when Reg Abrahams an elder from the Wathaurong Aboriginal Cooperative glanced my way as he was walking past. He approached me with ‘don’t I know you’ and we fell into conversation. I had met Reg a number of times but most recently at a Wurdi Youang open day. Wurdi Youang is a Reserve just west of Geelong that is culturally and environmentally significant to the Wathaurong. Reg is managing the development of the reserve, a process that involves revegetation, enhancing the priceless cultural features and working with Mt Rothwell Biodiversity Interpretation Centre to restore and translocate threatened flora and fauna. It’s a great project that will offer training for indigenous rangers and opportunities for the wider community to learn about indigenous culture. For more information about the Wurdi Youang stone circles and indigenous astronomy you could go to this link www.atnf.csiro.au/people/rnorris/papers/n258.pdf and for the indigenous perspective aboriginalastronomy.blogspot.com.au/2011/03/wurdi-youang-aboriginal-stone.html Reg was somewhat bemused as he had just been informed that his planned 30 minute slide presentation had to be compressed to 5 minutes. He would be on the big stage in an hour, after Don Burke who was keynote speaker for the afternoon. No one would consider asking Don to shorten his presentation to allow Reg to have more time. I should add that this was the only time in the whole conference that had been allocated to Indigenous Landcare Stories.  A tradional shelter built of stone and wattle branches at Wurdi Youang near Geelong, Victoria A tradional shelter built of stone and wattle branches at Wurdi Youang near Geelong, Victoria Reg must have been used to this sort of treatment because like Barak and the people of Coranderrk, he was philosophical and compliant. He was not angry or vindictive, two emotions that he had a perfect right to express. I felt angry and vindictive on his behalf, but it didn’t let on. Reg gave his shortened presentation with confidence and good humour. Later at question time he mentioned that the Indigenous Ranger program was going to end in 2018. The Landcare audience of several hundred expressed their dismay for the short-sightedness of 'the powers that be' Reg was joined on stage by three indigenous women who also told their stories over the next twenty five minutes. Aunty Esther Kirby from Barham on the Murray River spoke with love and sincerity about the old River Red Gums on the river and the healing properties of local plants. Her willingness to show any visitors around and teach them about culture, plants and bush foods was very moving. Don Burke was so stirred that he asked if he could be inducted into her tribe and become an honorary aborigine. The indigenous community have so much to teach Landcare about their deep connection with the land and how it can be managed with respect. I hope that at future National Landcare Conferences, one of the four themes that spans the two days will be ‘Indigenous Landcare’. An allocation of half an hour for the full two day conference was a sad reminder that attitudes have changed little toward the first Australians in the 180 years since white settlement.

1 Comment

kaye Rodden

16/12/2016 01:19:59 pm

A very timely reminder Steve that we need to build our partnerships across the landscape... I would like to share this if I may... across a broader landcare community.. let me know if this is OK?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed