Recreating the Country blog |

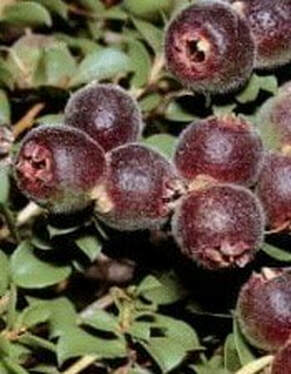

A mixed banksia planting for the cut flower market A mixed banksia planting for the cut flower market Setting the scene - a little piece of heaven The Grey family set off late one morning with a packed picnic lunch. Their rattly old mustard coloured Landrover ute carried them to their favourite place to picnic and it was on their own farm. It was a natural area of about 15ha fringed by an ephemeral creek that passed through the bottom corner of their 500 acre property. Their picnic spot was on a permanent spring fed water hole. Here they could sit in the shade, swim on hot days or simply lay back and listen to the wonderful variety of birdsong. It was their own private piece of heaven. After the picnic lunch their dad said, “Hey kids, I’m going to cut some firewood, why don’t you pick some of those beautiful banksia flowers for tomorrows farmers market”. Tristan and Nicola were twelve and fourteen now and they could only vaguely remember helping to plant the bush block when they were toddlers. Their dad would dig a hole for them to plant their very own trees to care for. These days they were secretly very proud of how big their trees had grown. One year they helped their parents plant several big patches of different Banksias in the bush block. Now the flowers from these shrubs were in demand at the local farmers market. They would bunch the different flowers together with some Silver-leaved Mountain Gum leaves (Eucalyptus pulverulenta) and sell them for $5. People would be waiting for them to arrive at the market so their fifty bunches of banksias would sell in no time.  The Mountain Pigmey Possum, Burramys parvus, is critically endangered. The Mountain Pigmey Possum, Burramys parvus, is critically endangered. Why build income streams into biodiversity plantings? In Revegetation – mimicking nature (February 2019 blog) I outlined a simple design system that imitates patterns in nature and recreates rich and biodiverse ecosystems (biorich). A critical feature of biorich systems is that their dimensions are larger. Ecologists agree that to support a diversity of wildlife, including rare and endangered species, corridors and revegetation plots have to be at least 50m wide and more than 10ha in area. Linking up these areas to allow species movement and migration is also critical to their long term survival. With so many of our wildlife drifting toward extinction, how can we create these necessary significant landscape transformations in the shortest time possible? It’s already a few seconds to midnight and the clock is ticking. A key first step in resolving this dilemma is convincing landowners across the country to participate. We need to provide the motivation for landowners to allocate large parcels of land to native grasslands, woodlands and forests. To become part of a radical shift in direction for land development and land management. Stewardships funded by governments could be part of the answer. This system pays farmers to preserve natural areas and not to farm. It’s a great way to ensure that remnant vegetation stays healthy and sustainable. The catch is it will cost the taxpayer a lot of money, though I think it would be money well spent. This solution also needs the political will in Canberra to adopt this promising solution on an Australia wide scale. Read more about stewardship here> Another solution is to add real income earning opportunities into biodiversity plantings. This will provide tangible incentives at the grass roots level. My view is that including up to 20% income generating plants with 80% biodiverse indigenous plantings would provide a good income to landowners as well as excellent wildlife habitat.  A small plot of Ironbarks, Eucalyptus tricarpa, form pruned in a trial plot in central Victoria. A small plot of Ironbarks, Eucalyptus tricarpa, form pruned in a trial plot in central Victoria. How to make income from biodiversity plantings Adding ‘useful’ plants to biodiversity plantings makes a lot of sense. These plants can provide products for the landowner for personal use or an alternative income stream. These same ‘useful’ plants will also provide excellent habitat and food for wildlife. A well designed biodiversity planting will support diverse and numerous wildlife including local endangered species of birds. It would also regenerate and self-perpetuate like the natural bush. The perfect biodiversity planting mimics natural bush in composition and form. It is diverse, layered, connected and importantly planted in clumps/groups of the same species. Read more in Revegetation – mimicking nature Adding up to 20% as ‘useful’ plants (that may be either indigenous, introduced natives or exotics) doesn’t compromise these fundamental biorich design principles. Cut Flowers In our story, the banksias species in the Grey family’s bush block were selected for the cut flower market and would provide both income and habitat. Wildlife would benefit from their dense shrub layer, their delicious nectar and the protected nesting sites that they provide. Thinning is a natural process Also Tristan and Nicola’s dad was thinning clumps of tall indigenous eucalypts for firewood. This process mimics a natural event in woodlands. Canopy trees are regularly blown down or damaged by strong winds. What looks a destructive event actually stimulates diversity and new life. Soil disturbance germinates seeds giving life to new plants. Opening the tree canopy lets in more light, accelerating the growth of germinating seedlings and other smaller plants. The 15ha revegetation site in our story has 80% indigenous plants. Because it mimics nature, there would be at least 20 species selected from 10 genera and importantly 7 families. Many of these indigenous plants have uses and income potential. Timber production For example ‘box’ eucalypts, stringybarks, ironbarks, produce valuable timbers. These can be thinned for personal uses like firewood, fence posts, and craft wood production. Some mixed farms now have small mobile timber mills for slabbing logs into planks for weatherboards, flooring and furniture. This is also a very effective way of taking carbon out of the atmosphere for many decades. Have a look at Agroforestry guru, Rowans Reid’s information site on milling timber> Seed orchards Some indigenous plants are becoming very rare and can be planted as seed orchards of rare and endangered plants. These plantings will be a critical (and potentially profitable) source of seed for future revegetation works. Same species grouping ensures good pollination and maximises seed production. It also makes harvesting convenient for man and ‘beast’. At the biorich demonstration site at Lal Lal, rare and endangered local forms of Silver Banksia, Banksia marginata and Bushy Needlewood, Hakea decurrens were planted in 2015. Seeds from these plants could be collected and sold to the Landcare community for use in revegetation. Though in this example the Ballarat Region Treegrowers, who manage the Lal Lal site, would likely donate the seeds.  Edible Muntrie berries, Kunzea pomifera Edible Muntrie berries, Kunzea pomifera Historic uses of indigenous plants Many indigenous plants have been historically harvested for their leaves, flowers, fruit, seeds/nuts and even roots. The First Australians knew and cultivated these resources and made sustainable use of them for more than 2,000 generations. To them every plant and animal had an ecological purpose, a use and a spiritual significance. Early settlers observed how the local indigenous people used plants and experimented themselves. Some examples of these in coastal areas are;

agreeable……the fruit is rich, juicy and sweet.”

Form pruning Spotted Gum with hand tools to improve the future value of the saw log Form pruning Spotted Gum with hand tools to improve the future value of the saw log Profitable Australian native plants The other 20% of non-indigenous plants can be added for personal use or for their commercial potential. These trees, shrubs and herbs are also planted in same species clumps for ecological and convenience reasons. Growing Australian hardwoods For example, a traditional forestry timber species like Spotted Gum, Corymbia maculata, can be planted in clumps of 10 to 50 trees. These trees will provide food and habitat for wildlife and could return up to $400/20 year old saw log at current prices. They would need to be thinned and form pruned for maximum returns, so convenient vehicle access is important. See this introduction to form pruning here> Many other Australian hardwoods are in demand for building, furniture and craft use. See this site for Australian timbers, uses and to see examples of their beautiful wood> Other examples of economic uses for native plants include;

The commercial opportunities for these plants and many others like them are still being explored and developed. They can be easily incorporated into biorich plantations as large clumps which make them convenient to access for maintenance and harvest. I have written more on the topic of biodiversity and profit here>  Quandong, Santalum acuminatum ripe and ready to pick. Their flavour is an exotic blend of lime and rhubarb. Photo courtesy of the ABC Quandong, Santalum acuminatum ripe and ready to pick. Their flavour is an exotic blend of lime and rhubarb. Photo courtesy of the ABC The amazing Native Peach and Sandlewood The Quandong or native peach, Santalum acuminatum, grows on a small tree and is valued for making chutneys, tarts and pies. It is now mostly found in the dryer inland parts of Victoria and South Australia but there is evidence that it grew as far south as Geelong and Melbourne before white settlement. The Quandong was being trialled by the CSIRO at Quorn in SA in the 1970’s for its commercial potential. Of the 200 trees in the trial, two had exceptional flavour and commercial potential. There are now 25 commercial orchards in Australia growing Quandong fruit for sale. Read more about quandongs here> A close relative of the Quandong is the Sandlewood, Santalum spicatum. This small tree is highly valued for its aromatic wood that is prized for the production of incense and perfumes. It played a pivotal role in the survival of the infant Western Australian Colony in 1844. It also produces delicious edible fruit and nuts. The nuts produce a fine oil, traditionally used by indigenous Australians as a liniment for body aches. Click here to read more about its history and commercial production in Australia. Read more about sandlewood here> Both the quandong and the sandlewood are parasitic trees that attach their roots to other nearby plants. The quandongs at Quorn were happily growing on couch grass, but usually they are associated with acacias which gives them a remarkable drought resistance. A mixed planting incorporating sandlewood at Echuca included both shrub and tall wattles as host plants (see images below - click to enlarge and read the full caption). Australian wildlife need landscape reform Larger, wider, connected biodiversity plantings that mimic nature are what our wildlife desperately need. When we consider that most of Australia’s land is privately owned it’s clear that incentives are needed to drive a fundamental attitude change about revegetation. A change that accepts that biodiversity and profit are compatible, desirable and necessary to achieve significant landscape reform. Farmers are small business managers who need to make their enterprises pay. Diversifying into sustainable biorich shelter belts will protect farms from extreme weather events and return significant incomes. It will also make an important contribution to the environmental reforms that Australian wildlife desperately need to survive into the next decade.  Biodiversity and profit - creative thinkers pushing the boundaries Two Victorian families turning the bounty of seeds from native plants into income

4 Comments

14/5/2019 03:39:04 pm

I enjoyed reading the article while learning things about biodiversity which I really need since I am a florist at CFA and nature is part of career.

Reply

Steve

8/6/2020 11:45:55 am

Hi Allan,

Reply

Michael Butler

7/6/2020 08:34:38 pm

Great article truly motivated me thank you

Reply

Steve

8/6/2020 11:53:17 am

Hi Michael,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed