Recreating the Country blog |

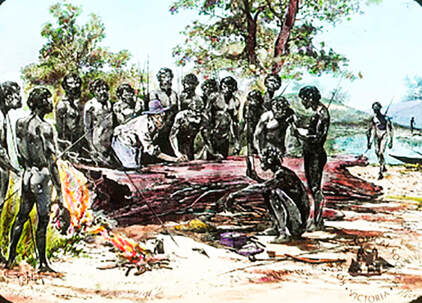

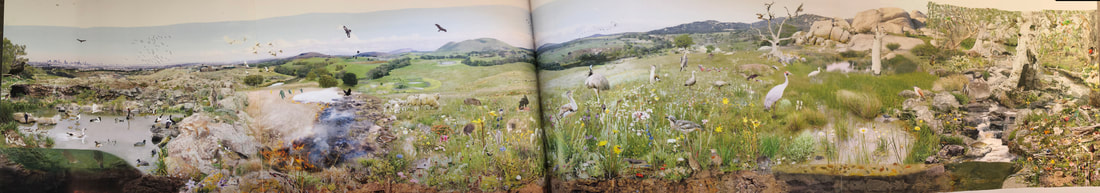

Philosopher Tao Tzu Philosopher Tao Tzu Restoring native grasslands - where to start? When faced with a daunting challenge like restoring native grasslands from a patch of bare earth or a paddock full of exotic weeds, sometimes the wisdom of a great sage can light the way forward. I couldn't do better than the often quoted words of the Taoist philosopher Tao Tzu; ‘The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step’, His well-chosen words help to shrink the broad focus of a big challenge like grassland restoration, to a goal that is much more achievable. Though in the context of grasslands, Tao Tzu might have said; ‘Restoring a native grassland starts with sowing a single seed.’  The first settlers to Victoria brought sheep in large numbers. They overgrazed and overstocked these fragile landscapes. The first settlers to Victoria brought sheep in large numbers. They overgrazed and overstocked these fragile landscapes. Glimpses into the past - What history can teach us? The year is 1883, a little over forty years after Victoria’s ancient and fragile landscapes first felt the pressure of thousands of hard-hooved animals. Pioneer Edward Curr witnessed that indigenous grasses were already in rapid decline; ‘The most nutritious grasses were originally the most common; but in consequence of constant over-stocking and scourging the pastures, these have very much decreased, their places being taken by inferior sorts of weeds introduced from Europe and Africa.’ The signs of degradation and loss could be seen at the beginning. Edward Curr describes a destructive and careless system of farming that would have caused the loss of many plant species and the ecologies that they supported.  Geelong's Traditional Owners thought that John Batman was asking permission to camp and hunt on their land. They would never have sold their traditional lands. Geelong's Traditional Owners thought that John Batman was asking permission to camp and hunt on their land. They would never have sold their traditional lands. What John Batman saw John Batman sailed into Port Phillip Bay and walked ashore at Indented Head on the Bellarine Peninsula on 29th May 1835. He wrote in his diary; ‘…nearly all parts of its surface covered with Kangaroo and other grasses of the most nutritive character, intermixed with herbs of various kinds.’ It’s surprising that Batman was able to make these enthusiastic observations in late May, which is a time when the spring blooms of wildflowers are long gone and most indigenous plants are dormant. Many are hidden underground as tubers or grasses and herbs that are no longer looking at their best. Two days later, after a 32 km walk east from Point Henry, Batman described the vegetation on Mt Bellarine; ‘…very rich light black soil covered in Kangaroo Grass two feet high and as thick as it could stand, good hay could be made in any quantity. The trees were not more than six to the acre, and those small sheoak and wattle. I walked for a considerable extent and (it was) all of the same description.’ It’s likely that Batman had one eye on the rolling hills of the Bellarine Peninsula and the other on marketing his proposed new settlement to the members of the Port Phillip Association. We know he promoted the landscapes around Geelong very well, from the tidal wave of new settlers that arrived soon after his deceitful and fraudulent 'land purchase' from the Traditional Owners, who would never have agreed to hand over the lands of their ancestors.  Women digging Myrnong, Yam Daisy at Indented Head. Original sketch by John Helder Wedge 1835 Women digging Myrnong, Yam Daisy at Indented Head. Original sketch by John Helder Wedge 1835 The changes to grasslands were swift and overwhelming The rapid changes to the vegetation around Geelong are shown by the early loss of an important staple food of the Wadawurrung. It took only four years for the women of the Bangali Clan of the Bellarine Peninsula to report that the Yam Daisy, once plentiful and widespread, had already become difficult to find. This same intense grazing pressure from flocks of sheep, their population doubling every three years, would have affected other plants with edible roots like the Chocolate Lily, the Bulbine Lily and all the species of orchid. We know that the sheep were so fond of these edible roots that they unearthed them by digging with their hoofed feet. The leafy herbs would have also succumbed to this new and much more intense grazing pressure of sheep and cattle. Only the toughest and least palatable of the native grasses and forbs would have survived this severe level of disturbance. The plants had evolved with kangaroos, wallabies and emus that grazed more lightly for a shorter period and then moved on, creating a grassland mosaic of different ages and lengths.  The Sunshine Orchid was once very common. Now only 37 plants remain The Sunshine Orchid was once very common. Now only 37 plants remain A more recent story illustrates how gradual change can be just as devastating to grasslands. The Sunshine Orchid, Diuris fragrantissima, described as dizzyingly beautiful, was so prolific in the western suburbs of Melbourne that it was known as 'Snow in the Paddocks'. An indigenous woman could dig enough of its sweet tubers in one hour to feed her family for a day. This regular harvesting with digging sticks made the soil loose and spongy, according to early settler records - a far cry from the hard and compacted basalt soils west of Melbourne today. Before the 1950s, locals would collect large bunches of the orchid blooms for their fragrant flowers. These orchid rich soils were ploughed, scraped, compacted, subdivided and finally built on. Now there are only 37 closely guarded Sunshine Orchid plants left alive in a location that remains a well-kept secret.  Black Thursday bushfire of February 6th 1851 Black Thursday bushfire of February 6th 1851 A 'new' fire changed the vegetation The termination of Traditional Owner management practices would have also changed the composition of the ground flora. Early settler descriptions of the burning practices on the Bellarine Peninsula give important insights into their cool burning method; ‘…their burning practice was random enough to maintain a wide variety of plant species and to keep the woodlands of the Bellarine Peninsula open and grassy.’ This all changed soon after 1835 when fires across the Victorian landscape became much hotter. This would have had a substantial effect on all native plants. In February 1851, one-third of Victoria endured perhaps its first destructive wildfire for millennia. Many flora and fauna species would have declined and disappeared under the unfamiliar forces of this new pattern of uncontrolled and hotter fires. Note on studies of historic fires: Core samples of lake sediments show that carbon levels increased dramatically soon after the white races occupied Australia. These studies provide clear evidence that the practice of strategic Traditional Owner cool burning prevented the out-of-control hot fires that have become a familiar and devastating manifestation of our Australian summers.  Modern day grasslands are likely to be quite different to the pantry-lands and medicinal herb-lands of pre 1835. Photo Dale Smithyman Modern day grasslands are likely to be quite different to the pantry-lands and medicinal herb-lands of pre 1835. Photo Dale Smithyman Do we know what our local vegetation looked like before 1835? To give you a sense of what was here before, native 'grasslands' could have been more accurately described as 'pantry-lands' or 'medicinal herb-lands'. This is because the Traditional Owners managed grasslands for their traditional uses as food and medicines, as well as the ecologies that the diversity of plants supported. Some of our best examples of remnant grasslands are found on roadsides, sustained by annual CFA burning to create firebreaks. Though, their practice of spring burning favours some plant species over others that need autumn burns, less frequent fires or cooler burns. This can be seen at the Rokewood cemetery, which is dominated by native herbs like its famous Button Wrinkewort, Rutidosis leptorrhynchoides, and has fewer native grasses. The annual spring CFA burning pattern has prevented grasses and some forbs (definition below) from flowering, setting seed and reproducing. This isn’t a criticism of the fine work that generations of country firemen and women have done to maintain this grassland and reduce fire risk locally. Their work has helped us understand how different patterns of burning can favour various plant species. Considering the dramatic changes in grazing pressure and burning temperatures since 1835, it’s probably not possible to find pristine remnant grasslands, exactly like those that were present two centuries ago. My own view has changed and I am now tempted to say that the composition of modern remnant grasslands is likely to be quite different to what was here pre white settlement. I feel we have very likely lost more species than we like to admit and the species grouping within plant communities has changed significantly. So here it is in a nutshell; ‘The remnant indigenous grasslands of Victoria, that we consider being in good condition, are likely to be floristically quite different to the grasslands that existed before the white races arrived in 1835?’ (A forb in botany is a flowering native herb. It excludes grasses, sedges and rushes as well as woody stemmed plants like shrubs and trees. Here is this handy rhyme to help you appreciate an important difference between a sedge, a rush and grass - 'sedges have edges and rushes are round, grasses have elbows that bend to the ground') To some of you, this may be an heretical statement, to others I’m likely stating the obvious. Though, it leads nicely into my next suggestion; Perhaps it’s time that we accept that we can't turn back the clock to a time before 1835. We should protect all surviving grasslands of course. The time has come to create new, robust and ecologically diverse modern versions of the 'lost grasslands of Victoria'. If we lay the right foundations and manage them with Traditional Owner style cool burning, Mother Nature will step in and guide its evolution towards a healthy sustainable balanced mix of species. Tao Tzu has something wise to say about this proposition as well; ‘Nature doesn’t hurry, yet everything is accomplished.’  In Restoring Native Grasslands - part 2, you can read the success stories of scientists and farmers who have restored grasslands.  Why couldn't this be an Australian backyard? Why couldn't this be an Australian backyard? In Restoring Native Grasslands - part 3, I’ll set out a simple method of replanting native grasslands. Here is a glimpse of part 3; You have returned home from a community meeting, inspired to plant a native grassland on your own back lawn. After a morning of weeding, you have carefully removed all the grass from a patch the size of your four-year-old’s paddling-pool, so that it’s now loose bare soil. Your grassland champions from the nursery are well-watered and ready to plant, and a group of friends will soon arrive to be part of what promises to be the beginning of a new era. An era when the local plants begin to return to backyards across the country. Curiously, you have a 2 kg bag of white sugar to spread on the soil before you plant. Sweet ??!! You and your friends are part of a new nationwide movement to restore the lifeblood of the land – by planting back the remarkable plants that have made Australia so floristically unique.  For some background reading on grasslands - Grasslands. Why we're losing the battle to save them

7 Comments

Dale Smithyman

14/9/2022 02:09:18 pm

Great article Steve. I can't wait for the next instalment!

Reply

Steve

15/9/2022 08:18:43 am

Thanks Dale. It should be worth the wait.

Reply

John Delpratt

14/9/2022 03:22:58 pm

I'm with Dale - looking forward to Stephen's contribution to the critical issue of expanding native grassland communities. There's plenty of room available and these species generally do very well when given a fair go.

Reply

Steve

15/9/2022 08:45:03 am

Hi John,

Reply

Kelly Scott

24/10/2022 01:33:17 pm

Hi Steve and John! I may have an answer to this - I read recently in the William Todd Journal that tambourn is a Wadawurrung word and may refer to the roots, and murnong refers to the leaves and flower. I don't have a link sorry, as I read it in the Geelong Heritage Centre.

Steve

24/10/2022 04:08:46 pm

That's a great find Kelly. When I get the chance, I'll borrow Todd's journal and have a look through. I remember being fascinated with his record of the first contacts at Indented Head when I read it years ago.

Reply

Kelly Scott

25/10/2022 09:04:17 am

I do hope that's the right book now haha but ask the staff there, they're incredible and can find anything you're after!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed