Recreating the Country blog |

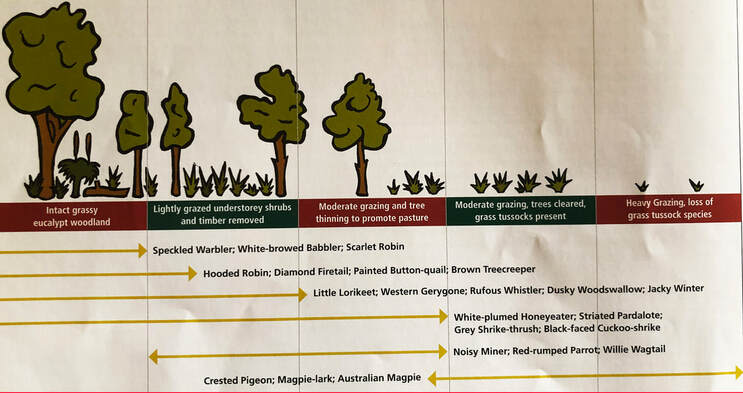

Vegetation corridors, biolinks, vegetation highways - connecting the dots in the new decade27/1/2021 We’ve all played join the dots when we were kids and I remember being amazed and excited as the image of a kangaroo or a Wedge-tailed eagle took shape. Then came the even more interesting challenge of adding the colour that brought the image to life. One of the biggest challenges facing Landcare this decade is connecting the dots and dashes. This is an essential process that will breathe more life into existing plantations (the dashes) and the remnant paddock trees (the dots).  We have created islands of trees in open seas of cropping and grazing paddocks We have created islands of trees in open seas of cropping and grazing paddocks A lot has been achieved over the past four decades putting trees on farms. We now have more shelter and we have restored some of the lost biodiversity. Though if we examine these planted landscapes on Google maps what do we see? A countryside of disconnected dots and dashes. We have created islands of trees in open seas of cropping and grazing paddocks. Breathing more life into plantations hints at the truly remarkable transformation that would take place. The many missing faces of Australia’s birds, mammals and insects that have been just surviving in isolation would appear when safe passage from plantation to plantation is established.  Charles Darwin recorded fewer species on the Galapagos Islands than on similar continental habitats Charles Darwin recorded fewer species on the Galapagos Islands than on similar continental habitats The island effect Charles Darwin on his journey to the Galapagos Islands noted a reduced diversity of species on small islands; ‘The species of all kinds which inhabit the oceanic islands are few in number compared with those on equal continental areas’ This ‘island affect’ has been observed again and again in studies. A study of Lord Howe Island in 1984 showed that birds on islands face fifty times the normal threat of extinction because of their isolation. If you have lived in an isolated country town you know how difficult it is to restock the pantry. Thank goodness we have safe roads to travel for supplies.  A healthy ground layer in the Amazon Rainforest. Photo Rhett A Butler A healthy ground layer in the Amazon Rainforest. Photo Rhett A Butler What clearing the Amazon rainforest in Brazil can teach us about island ecology? A study of the Amazon rainforest confirms the fragility of island ecosystems. Scientist Tom Lovejoy studied forest plots of different sizes that were saved from clearing. Initially he found that birds were able to move from the newly cleared areas of forest into the retained refuge plots. However the pressures of overpopulation on these ‘islands’ eventually caused bird populations to decline. And they kept declining particularly if there was an interdependence with other insect, bird or mammal species. Birdlife Australia has been reporting on the ‘State of Australia’s birds’ for two decades and drew similar conclusions from their extensive observations. Clearing woodlands and forests causes the loss of an estimated 3,000,000 woodland birds each year. Small numbers survive in remnant small pockets for a short time but they are isolated, cut-off and slowly die out. We abuse the land because we see it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see the land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect. Aldo Leopold 1948  Scattered paddock trees need to be within 'line of site' for insects and birds to migrate Scattered paddock trees need to be within 'line of site' for insects and birds to migrate Paddock trees support the ‘island hoppers’ Paddock trees are vegetation islands on farms that provide homes for wildlife and sleepovers for migrating species. If paddock trees are within ‘line of site’ (25 m – 100 m), they provide critical links in the vegetation chain that supports the migration of many species of insect and birds. They can use existing old trees as stepping stones as they follow their habitual migration path for food or warmer weather. But these old trees are dying out, and they aren’t being replaced. Click here to read about how to protect and restore paddock trees Can you imagine the frustration of driving to your favourite camping destination only to find that the road’s been washed away by a recent flood? Imagine if the sign said ‘sorry, but this road has been permanently closed, you have to turn back.’ What if you depended on this road to access essential items, what then? Paddock trees provide so many key benefits to biodiversity and to farming that planting them across our rural landscapes is a logical first step to re-establishing the critical missing vegetation connections.  As ground litter, native grasses, shrubs and trees are cleared, bird communities shrink and change. Ref: The State of Australia's Birds, 2005. Birdlife Australia As ground litter, native grasses, shrubs and trees are cleared, bird communities shrink and change. Ref: The State of Australia's Birds, 2005. Birdlife Australia Paddock trees need companion plants Improving the habitat under and around paddock trees is critical. It makes an enormous difference to their health and the diversity of wildlife that they support. Planting small indigenous shrub species & grasses under a tree’s canopy and taller indigenous understorey trees beyond the canopy builds in the layers of vegetation needed by the majority of reptiles, amphibians, small mammals, woodland birds and insects. To read more about creating vegetation layers click and scroll down here The extra birds and insects that are attracted by these ‘companion plants’ help to control insects that defoliate the paddock trees and attack nearby crops and pastures. Including some nectar-producing understorey species will help to support the many of insect-eating birds, lizards, mammals, parasitic wasps, flies, and spiders that are necessary to keep the defoliating insects in check. ‘A healthy bird community removes between 50% & 70% of the leaf-feeding insects from patches of farm trees and so plays a valuable role in keeping those trees alive’ Birds on Farms. 2000. Geoff Barrett To read more about paddock trees; Paddock trees - part 1. Their beauty and their bounty Paddock trees - part 2. Their economic benefits on farms Paddock trees - part 3. How to protect, regenerate and replant  The Regent Honeyeater is one of Australia's most handsome honeyeaters. It relies on Box Ironbark forests and the forests rely on the honeyeater The Regent Honeyeater is one of Australia's most handsome honeyeaters. It relies on Box Ironbark forests and the forests rely on the honeyeater Linking shelter belts Shelter belts, woodlots and biodiversity plantings support a different group of wildlife that need the seclusion and resources of wider, mixed plantations. Linking them is a powerful way of providing the vital feature of continuous vegetation connections. The Regent Honeyeater story illustrates why we need to establish corridor links. The Regent Honeyeater, Xanthomyza phrygia is one of Australia’s most handsome honeyeaters. It has evolved over the millennia to feed almost exclusively on the nectar of Box Ironbark woodlands and forests. Box and Ironbarks are hardy eucalypt species that originally formed a continuous corridor from Rockhampton in Queensland, through NSW & Victoria and on to Adelaide, SA. The Regent Honeyeater could once be seen flying overhead in flocks of hundreds as they followed the nectar flow of these eucalypts on their annual migratory journey from Queensland to South Australia. Now most of the box and ironbark trees have been harvested for their durable and hot burning timbers, leaving only small isolated patches of the original corridor. With their habitat diminished and the opportunity to migrate interstate no longer available, the Regent Honeyeater population went into decline. By the early 1990’s less than 1,000 birds had survived. The honeyeater was just the tip of the iceberg as many other bird, mammal and insect species were part of this remarkable ecosystem. A small snapshot of the other associated species that relied on the corridors of Box Ironbark woodlands were the Grey-crowned Babbler, Brush-tailed Phascogale, Sugar & Squirrel Gliders, Wood White & Imperial Jezabel Butterflies.  Restoring the Box Ironbark woodlands at Benalla is a success story. Its only a small fragment of the original corridor from Queensland to South Australia Restoring the Box Ironbark woodlands at Benalla is a success story. Its only a small fragment of the original corridor from Queensland to South Australia Significantly the annual migration of the Regent Honeyeaters was critically important for the Box Ironbark forests and woodlands. It enabled them to adapt to the dramatic changes in climate experienced during the transition from the last ice age 10,000 years ago to the warmer climate we know today. The honeyeaters carried Box and Ironbark pollen from Queensland to South Australia and back again giving the trees the genetic coding they needed to adapt to a rapidly changing climate. These trees no longer have the Regent Honeyeaters and their cohort fauna to provide this service and will not be able to adapt to the current climate change challenge. Ecologists now talk about ‘composite provenancing’ to help trees adapt. This means planting some trees of the same species sourced from locations that are 2 degrees warmer to provide the necessary genetic adaptions to our warming climate. I'm sure you'll agree that this can only be seen as a stopgap measure that could never replace the complex system that mother nature had designed. Fortunately the Regent Honeyeater project based in Benalla, Victoria has reversed the decline of honeyeaters locally. Since 1996 the Landcare community supported by local schools and the community have restored over 1,600 ha of Box Ironbark habitat. Regent Honeyeaters and Grey-crowned Babblers are now commonly seen around the Lurg Hills near Benalla After a visit to the Regent Honeyeater project I published a review in the Australian Forestry journal. Click here to read  Ecologists now recommend that corridors need to mimic the natural bush, be wider and more diverse to be effective for most of our native fauna. These 'biorich' corridors can also provide a significant income to farms. Click here to read more about corridor design that mimics nature as well as providing significant income to farms In 2019 the United Nations declared 2021 – 2030 the decade of ecosystem restoration. We can each play our part by planting habitat on our properties, whether they are small and urban or large and rural. If you have some acres, now it’s time to play the adult version of connecting the dots and dashes on an aerial view of your property. Making these links will allow wildlife to forage more widely for food and to migrate safely. Safe migration of birds and insects is also essential for both flora and fauna to evolve and adapt to our current climate change crisis.

4 Comments

Michele Lockwood

30/1/2021 07:27:10 am

Thank you Stephan for another edition packed with inspiration and insight to help make informed decisions in better managing areas for wildlife.

Reply

Steve

4/2/2021 02:46:31 pm

Hi Michael,

Reply

Grace

7/2/2021 07:45:10 am

Hello and thanks for sharing this information.

Reply

Steve

28/2/2021 03:06:37 pm

HI Grace,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed