Recreating the Country blog |

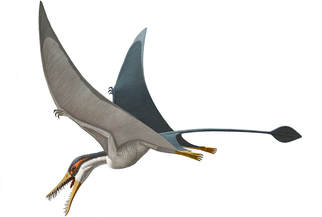

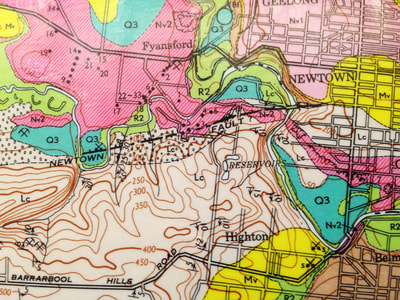

Australian born Rod Taylor is the time traveler the 1960's film based on H G Wells classic story 'The Time Machine' Australian born Rod Taylor is the time traveler the 1960's film based on H G Wells classic story 'The Time Machine' H G Well’s classic story ‘The Time Machine’ explores the idea of visiting past worlds in a beautifully crafted time machine. A far less romantic way of discovering past worlds relies on the sciences of geology and paleontology. These methodical and often painstakingly slow disciplines provide windows into past worlds through fragments of evidence found in ancient rocks  The Barrabool Hills started as an inland lake environment in the Cretaceous period 135 million years ago. The grevillia like flowers of primitive members of the protea family began to appear at that time in Australia. The Barrabool Hills started as an inland lake environment in the Cretaceous period 135 million years ago. The grevillia like flowers of primitive members of the protea family began to appear at that time in Australia. There is a lot of ancient history hidden in the rocks of the Barrabool Hills and this history has played an important part in developing its unique landscape and vegetation. Let’s imagine we have borrowed the amazing time machine and it has carried us through many millennia in a matter of seconds to a time 135 million years ago when it all began. We’ve arrived and we’re mystified because we’re sitting in total darkness and the air is sharp and cold. We zip up our windcheaters and pull down our beanies to keep out the chill of a deep arctic winter in Gondwanaland. We shine our torches into the eerie darkness and see snow under the ghostly silhouettes of trees hugging the edge of a shadowy frozen lake. A dog sized animal ambles past sniffing the air curiously, its paw prints in the snow are strangely reptilian.  135 Ma ago in the Cretaceous period Australia was connected to Antarctica and part of the super continent of Gondwana 135 Ma ago in the Cretaceous period Australia was connected to Antarctica and part of the super continent of Gondwana 135 million years (Ma) ago Gondwanaland was a super continent made up of Australia, Antarctica, Africa, New Zealand and South America and it was sitting around the South Pole. Australia was so far south on planet earth that it experienced perpetual summers and perpetual winters lasting up to six months of the year, much like Norway, Alaska and the north of Finland experience today.  Primitive forms of the deciduous Gingko biloba were a feature of these ancient rainforests. Fossils of Gingko leaves have been found in the Barrabool Hills Sandstone Primitive forms of the deciduous Gingko biloba were a feature of these ancient rainforests. Fossils of Gingko leaves have been found in the Barrabool Hills Sandstone We touch the accelerator on our time machine and travel back another six months to the perpetual summer where the sun peaks through a cloudy sky. It feels like a crisp warm spring day in modern Australia, though the vegetation seems to be a more vivid green. A large platypus scrambles onto the bank and startled by our time machine turns and slides back into the lake. The presence of the platypus and the sight of a small polar dinosaur drinking at the lake’s edge confirm that this lake is freshwater. We notice that the dinosaur has large possum-like eyes for night vision in the arctic winter and a long tail reminiscent of a kangaroo. Its ability to hunt during the long winters suggest that it is warm blooded like the ancient platypus. We can now appreciate that the lake extends as far as the eye can see and is surrounded by a lush vegetation of ferns, cycads, clubmosses and horsetails, creating the understorey for a towering conifer rainforest related to the Wollemi Pine (family Araucariaceae), complemented by Myrtle Beech, Nothofagus cunninghamii and deciduous Gingko trees. Note 1 - Gingkos & Note 2 - Plant fossils>  Plants related to this ancient Silver Banksia grew in the Barrabool Hills when it was a rainforest 135Ma ago. Photo Anna Foley. Plants related to this ancient Silver Banksia grew in the Barrabool Hills when it was a rainforest 135Ma ago. Photo Anna Foley. The first flowering plants including the ancestors of the Banksia, Grevillea and Macadamia (Proteaceae family) were beginning to bloom in this prehistoric world but there were no familiar trees like the acacia, eucalypt and casuarina. This temperate humid climate produced a lush rainforest nourished by numerous rivers and streams. It is the time of reptiles and dinosaurs and the ‘birdsong’ of the flying dinosaurs (pterosaurs) is likely to have sounded like the rasping shriek of the White-faced Herons that frequent our present day wetlands. This unnerving sound echoing around the humid misty forest would have given this ancient place a pungent and menacing atmosphere. It was another species of small flying dinosaur (Archaeopteryx) from this same time that is likely to have evolved into modern day birds with their beautiful diversity of song.  The Barrabool Hills 'Freestone' has a beautiful warm colour as seen on this cottage in Ceres. The Barrabool Hills 'Freestone' has a beautiful warm colour as seen on this cottage in Ceres. In this ancient world the rivers and streams tumbled down from precipitous mountain ranges quite close to the inland lake. The sharp and angular sand grains found in today's sandstone tell us that the sand grains didn't travel far enough for their corners be to become worn and rounded. At the lake their rapid pace slowed and their sandy load was dumped around the shallow lake’s edge in extensive fan-like deposits. These deep sediments are the same grey mudstones and golden sandstones that we see today in roadside cuttings through the Barrabool Hills and the Otway Ranges. Note 3 – Ancient sands> The landlocked lakes steadily filled with sediment and plant material from the surrounding hills. Accommodatingly the lake bottom slowly subsides creating a shallow swampy environment that continued for millions of years resulting in sandstone and mudstone deposits of over 1,000 metres thick in some places. Note 4 - Barrabool Hills sandstone>  Flying dinosaurs like this late Jurassic pterosaur disappeared with 75% of life on earth when an giant asteroid hit earth about 35Ma ago. The pterosaurs may have evolved into modern bat species. Flying dinosaurs like this late Jurassic pterosaur disappeared with 75% of life on earth when an giant asteroid hit earth about 35Ma ago. The pterosaurs may have evolved into modern bat species. Our time machine carries us forward to 85Ma ago and now the super continent of Gondwana is breaking apart. Australia is beginning to split away from Antarctica, the beginning of a long process that takes another 55Ma. Eventually Australia drifts free and begins a slow passage north toward the equator and a warmer a dryer climate at about 1 cm/year gradually accelerating to its present dizzying speed of 6cm/year. About 35Ma, an immense comet, estimated to be 10 km wide, hit planet earth near the Gulf of Mexico. It is thought that its impact would have been equivalent a billion Hiroshima bombs. This comet changed life on earth forever and caused a mass extinction of three quarters of all plants and animals. Dramatically this comet brought to an end the era of the dinosaurs and the era of the mammal began. Earthquakes, volcanoes and the birth of the Barrabool Hills (added 7/8/17)  This modern earthquake in New Zealand resulted in over one meter rise. Further regular movements on this fault will produce a hill where a flat plane once existed This modern earthquake in New Zealand resulted in over one meter rise. Further regular movements on this fault will produce a hill where a flat plane once existed As time travelers we discover that as Australia drifted north its climate gradually warmed and dried. Australia experienced ice ages and a two hundred year drought. Eventually the seasons also changed from endless mild summers and dark freezing winters to the warm summers and mild winters with the transitional seasons in between that we know today. Australia’s unique flora and fauna began to emerge, adapt and evolve. It was around this time that the Barrabool Hills were born. Our time machine arrives at 30 Ma ago and we feel the earth shake violently. We're experiencing the first of a long period of earthquakes that lifts the ancient freshwater lakes of Gondwana above the surrounding area. These uplifted ancient lakes slowly form into hills which become surrounded by an invading sea. The Barrabool Hills become an island surrounded by shallow seas rich in marine life, which over deep time becomes the Waurn Ponds Limestone> These powerful earthquakes slide along fault lines in the sandstone and evidence of these faults can be seen today as steep hills at the southern edge of the Barrabool Hills running from Pollocksford to Ceres Bridge (the Barrabool fault) and Queens Park to Newtown (the Newtown fault). These faults have remained active to modern times and bit by bit the Barrabool Hills has been lifted more than 90 meters above the Geelong coastline. While the Barrabool Hills was being raised above the surrounding plains by regular earthquakes, its deep sandstone was being sculpted by extreme weather, including an ice age that begins 2.4Ma ago. At this time the earth’s climate became very cold and glaciers covered parts of southern Victoria. During this time, the night skies became a spectacular sound and light display as volcanoes erupted and shimmering hot lave flowed over the plains, filling river valleys. The lava blocks and moves rivers, creating many inland lakes. Volcanic eruptions continue throughout most of southern Victoria until a few thousand years ago, but it has very little effect on the Barrabool Hills that have been lifted high above the lava covered plains to the west.  The Barrabool Fault displaced the Barwon River which is just visible on the right of this image The Barrabool Fault displaced the Barwon River which is just visible on the right of this image Our time machine stops once again at 11,500 years ago, when the climate is beginning to warm significantly. So much so that the polar ice caps partly melt and sea level rises 120 m (1 m/100 yrs). From our elevated view on the top of the Barrabool Hills we watch the sea rush in and cover the vast coastal grassy plain to the east of Geelong, now called Port Phillip Bay. Tasmania also becomes isolated from Victoria as Bass Straight floods and the narrow land-bridge, regularly used by migrating land animals and importantly by the first Australians, is covered by the sea forever. It is 8,000 years ago and our time machine is just ticking over, allowing us to watch the Barrabool Hills slowly wear-down. This is a warmer, wetter period and small creeks rush down the slopes after heavy rains, eroding the ancient time hardened sands, carrying them north to the Barwon River. Once part of the Barrabool Hills, the Barwon River was pushed to the north as the hills rose. Regular upward fault movement of the Barrabool Hills energises the creeks, which cut deep into the sandstone. Gradually over time the undulating hills and the fertile valleys that we admire today assume their familiar character.  Drooping Sheoak woodlands were a feature of the Barrabool Hills in 1835 when they were first described. Drooping Sheoak woodlands were a feature of the Barrabool Hills in 1835 when they were first described. From freshwater lakes to abrupt hills, from sandy aquatic deltas to deep hard sandstone, these remarkable changes took tens of millions of years. Impassively and gradually, like an immense rudderless ark, the great continent of Australia journeyed from the Antarctic Circle to the equator, a passage that caused Australia’s climate to change slowly but radically. The Barrabool Hill’s lush towering conifer and gingko rainforests in a protected swampland have gone forever. It has given way to temperate grassy eucalypt and casuarina woodlands that have adapted well to strong winds, dry hot summers and mild winters. The plants of Guandwana have been replaced with a hardier mix of plants that is unique to the Barrabool Hills. How these modern plants have evolved and how they were modified by the first Australians, who arrived over 60 thousand years ago, will be explored in the next blog.  The Barrabool Hills vegetation. Part 2 – The arrival of Homo sapiens Fig. The huge Diprotodon is likely to have been part of the mix of fauna that lived in the Barrabool Hills over 60,000 years ago

1 Comment

|

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed