Recreating the Country blog |

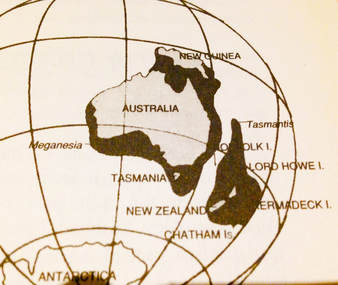

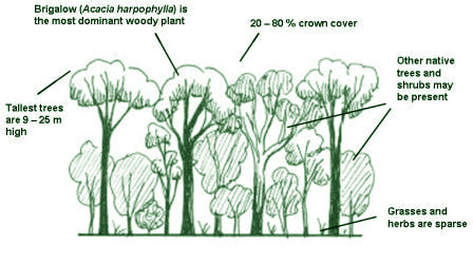

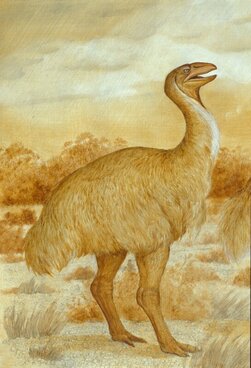

Meganesia was a land mass that included Australia, New Guinea and Tasmania Meganesia was a land mass that included Australia, New Guinea and Tasmania Meganesia. Homo sapiens first arrived in Australia about 60,000 years ago when the climate was colder and dryer. Evidence suggests that the Wadawurrung people have lived in the Geelong region more than 40,000 years. At that time the world was in the grips of the last great ice age. 'Ark' Australia, home to a remarkable and unique mix of plants and animals, was about 4km south of where it is today. It had been slowly drifting north for 30 million years after breaking away from Antarctica. 'Ark' Australia was then part of a greater land mass called Meganesia which included Australia, New Guinea and Tasmania and the low plains in between. Its time to climb on board our amazing time machine and travel back to the Barrabool Hills in the far south of the great continent of Meganesia. We arrive in late summer on a perfect windless day. The undulating hills are much as we know them today though we notice the animals are much larger and we are surrounded by a forest of tall acacias.  The largest diprotodon stood nearly 2 m tall and weighed 2000kg The largest diprotodon stood nearly 2 m tall and weighed 2000kg Australia's megafauna. Not far from where we're sitting in our time machine, a huge wombat like animal nearly 2 m tall (Diprotodon sp.) is tearing leafy branches off the tall broad-leaf trees. Its slow and rhythmical chewing is suddenly disturbed by a giant goanna that runs up the diprotodon's front leg and bites savagely into the surprised animal's thick hairy neck. The diprotodon instinctively falls to the ground and tries to roll onto the goanna, using its enormous weight as a defence against the veracious and powerful carnivore. The goanna rolls clear and the two animals stand motionless in a prehistoric standoff. The diprotodon bellows like an angry bull and stomps with an elephantine foot. The goanna thinks better of another attack and retreats at speed into the dense undergrowth.  Brigalow is an acacia species that provided the canopy for the 'dry' forests that were a feature of Australia 60,000 ya Brigalow is an acacia species that provided the canopy for the 'dry' forests that were a feature of Australia 60,000 ya Our attention shifts to the vegetation that surrounds us. We're sitting in a clearing but nearby is a thick dry forest dominated by acacias. The acacias are tall upright trees that look similar to the Blackwood, Acacia melanoxylon and Lightwood, A. implexa that grow in the Barrabool Hills today but euclaypts are only a minor species. Other trees we can see in the forest are Drooping Sheoaks, Allocasuarina verticillata Kurrajong (Brachychiton sp.), as well as the fruit laden Cherry Ballart, Exocarpus cupressiformis and Quandong, Santalum accuminatum. Brigalow forest This list of species mirrors the plants that make up the Brigalow dry forests of southern Queensland and northern NSW that are dominated by Brigalow, Acacia harpophylla. The Brigalow forests remain as an example of the composition of Australia's vegetation along the eastern states before the extinction of the megafauna. and before frequent indigenous burning caused radical vegetation change. Studies of pollen in lake sediments show that a fundamental shift from forests dominated by long living acacias started around 60,000 years ago. Increased carbon levels in these lake sediments indicate that more frequent fires brought about a shift from the fire sensitive Brigalow rainforests to fire loving plants. These are the very familiar eucalypts, shorter lived acacias, banksias, bursarias, Tree Violet and a diverse mix of grassland plants that all depend on regular burning for their long term survival.  The largest of all Australian birds, Genyornis newtoni, stood over 2m tall. Image - The Australian Museum The largest of all Australian birds, Genyornis newtoni, stood over 2m tall. Image - The Australian Museum Dr. Tim Flannery in his landmark book 'the Future Eaters' argues that when the first Australians arrived they found a continent dominated by large grazing and browsing marsupials. These included a marsupial rhino, diprotodons of different sizes, a marsupial lion, five species of extinct wombats and seven species of giant short-faced kangaroos. There was a giant species of mallee fowl weighing up to 7kg. and the largest of all Australian birds, a 200kg stocky flightless bird related to the domestic chicken. Flannerey describes these animals as walking composting machines. They browsed on the broad leafed trees and shrubs and they converted the leaves and stems into nutrient rich manures that were quickly incorporated into the soil by relatives of the dung beetle. Though Australia's southern climate was dryer, the soil was richer, with more nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur and humus. This well structured humus rich soil combined with the denser forest vegetation resulted in much less runoff and the plants making better use of the meager rainfall. Also the calmer weather created by these dry forest environments resulted in a cooler forest floor and less moisture loss from the plant leaves. Overall 60,000 years ago the trees and shrubs on the east coast of Australia needed less rainfall to survive and thrive.  The decline of the megafauna influenced change in Australia's vegetation and climate The decline of the megafauna influenced change in Australia's vegetation and climate The first Australians arrive When the first Australians arrived across the land bridge from New Guinea an estimated 60,000 ya, the animals had never seen humans and didn't recognise them as a threat. The megafauna were slow, practically tame and easy to hunt, so their numbers declined rapidly. Fossil records suggest that they were all extinct 35,000 - 40,000 ya. Flannery proposes that as the megafauna numbers declined, Australia's vegetation became overgrown and tangled because it was no longer being eaten. This added significantly to fuel loads, making hunting less convenient for the early Australians. Fire from lightening strikes would have shown them a way to manage the bush and open it up. Gradually the art of the cool burn evolved and this favoured the fire loving plants and not the food plants of the megafauna. So hunting and burning put the megafauna into a downward spiral toward extinction. Burning and the decline of the megafauna changed Australia's soils forever from nutrient and humus rich to nutrient and humus depleted. This is because burning removes nitrogen, sulfur and humus from the nutrient cycle. Our nutrient starved soils then became more erodible, a problem that was added to by the shift from dense Brigalow forest to less dense and more open eucalypt woodlands.  Heathland plants were well adapted to fire and poor soil. They quickly invaded as the broadleaf plants retreated. This ancient Tree Violet is a likely survivor of ancient heathlands. Heathland plants were well adapted to fire and poor soil. They quickly invaded as the broadleaf plants retreated. This ancient Tree Violet is a likely survivor of ancient heathlands. and Australia becomes dryer... The transition to eucalypt woodlands resulted in less rainfall inland, which was another nail in the coffin of the megafauna. This is because the forests of broad leaf plants transpire significantly more water vapour which aids cloud formation and rainfall well inland from the coast. The narrow dry eucalypt leaves release much less moisture into the atmosphere so inland areas became dryer as the forests of broad leaf fire sensitive plants disappeared. A dryer climate resulted in a gradual shift to a different vegetation. Waiting in the wings were the heathland plants that had evolved alongside the broad leaf forests. These plant communities had adapted to regular burning for at least 200,000 years and needed fire for propagation. They had developed toxic leaf chemicals that discouraged browsing by the megafauna to protect their meager reserves that were hard won from the poor soils where they grew. Heathland species like the banksia, hakea, tea-tree, paperbark, short live wattles and stunted eucalypts were ready to spread as the poorer dryer soils became more common and the local climate dried. In the Barrabool Hills the Golden Wattle, Acacia pycnantha, the Hedge Wattle, A. paradoxa, the Tree Violet, Melicytus dentatus and Sweet Bursaria, Bursaria spinosa were well adapted to fire and dry sandy soils. They can still be found on roadsides in the Barrabool Hills.  White Cypress Pine at the Leigh Gorge near Shelford. A rare plant community still surviving from the last ice age White Cypress Pine at the Leigh Gorge near Shelford. A rare plant community still surviving from the last ice age 20,000 to 12,000 years ago the last ice age intensified in all parts of Australia and temperatures dropped to an average of 6 degrees below present day. With so much water locked up as ice at the poles, rainfalls declined in Australia and the Barrabool Hills dried significantly more. This favoured drought and cold adapted plants like the White Cypress Pine, Callitris glaucophylla, and the Snow Gum, Eucalyptus pauciflora. Both these relics of the ice age can still be found within 20 Km of the Barrabool Hills. Other species that would have thrived in the cooler dry climate are Manna Gum, E. viminalis, Drooping Sheoak, Allocasuarina verticillata and the Black Wattle, Acacia mearnsii. The Manna Gum, Drooping Sheoak and Black Wattle are still present in the Barrabool Hills today and appear to have been important to the Wathaurong people. There is clear evidence that their cool burning techniques were designed to favour these trees. For example the Drooping Sheoak was described by John Helder Wedge, John Batman's surveyor, who explored the Barrabool Hills on 18th August 1835, as 'thinly wooded with sheoak for 3 miles'. This open woodland pattern is not natural to Sheoaks and must have been the result of strategic cool burns. The purpose of this burning pattern and findings in other historic records about the original vegetation of the Barrabool Hills will be explored in my October blog. Click on the heading below to read: The Barrabool Hills Vegetation. Part 3 - Its original and natural condition in 1835

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed