Recreating the Country blog |

|

In this blog Gib describes a Traditional Owner cool burn and looks at its cultural importance through the eyes of indigenous leaders. Gib argues that Australians could learn how to conduct cultural burns in a 'Fire Masters' course, taught and managed by indigenous experts. This would ensure that the method remains pure and achieves desired outcomes such as reduced fire risk in summer and restored biodiversity. Photos by Gib Wettenhall unless otherwise cited  Uncle Rod Mason, a Ngarigo elder and expert in Traditional Owner cool burning Uncle Rod Mason, a Ngarigo elder and expert in Traditional Owner cool burning Cultural burning as an agent of renewal At a traditional Aboriginal-style mosaic burn in autumn last year, 30 of us were counter-intuitively removing logs and large sticks within a 300 square metre area defined by a broad line of yellow spray paint. We were preparing a patch of grass and weeds for firing within open box woodland in north-east Victoria at a workshop organised by the Wooragee Landcare group. The man-in-charge issuing instructions was ‘Uncle Rod’ Mason, a Ngarigo elder who had learnt how to use fire growing up in the Western Desert. From a young age, his community had placed a box of matches in his hands and he grew in responsibility, along with everyone else in his language group, learning through experience when and how to deploy fire. Where Western culture breeds fear of fire, Uncle Rod relishes it as an agent of renewal: “You got to fire it! When you burn Country, it makes it brand new fresh.”  Dead wood was removed from under large gums to minimise 'dampening down' after the burn Dead wood was removed from under large gums to minimise 'dampening down' after the burn The principles of indigenous fire management Fire, we now understand, was the major tool employed by Aboriginal people to manipulate the landscape on a grand scale. They burnt to maintain vast grasslands to sustain mobs of kangaroos. They fired a patch in late summer to bare the soil so their underground larder of yam daisies and orchid tubers could surface. They set fire to hunt game, clear a path, attack an enemy, call a meeting, spiritually cleanse it. Uncle Rod described the three principles of Indigenous fire management that underpin patch burning continent-wide. He cited these principles as,

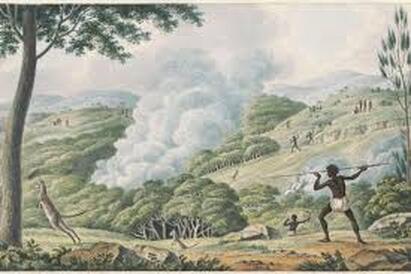

Reducing the fuel load was the reason Uncle Rod first fixed us with his intense gaze and oversaw the removal of logs and large branches from our defined patch of grass and weeds. Smouldering logs can burn for a long time and prove a fire risk, he pointed out. Two years prior, at a cultural burn at the Teesdale flora reserve, Uncle Rod and his team removed the dead wood from under the large gums at the back of the block. On the left hand side of the reserve where the CFA planned, at the same time, to demonstrate their cool burn techniques, no such precautions were undertaken. Their fire flared much higher and dampening down the burning logs proved a struggle. Next, Uncle Rod went down on one knee and made a small pyre of leaves and twigs. We were to dot these mini-bonfires at regular intervals throughout the patch. When these were spread throughout to his satisfaction, Uncle Rod tested the wind. “You got to trickle burn backwards into the wind,” he said. He lit the first mini-bonfire and gestured towards the neighbours we were to light up. They burnt low and slow into each other. A cloud of white smoke rose and enveloped us.  Uncle Rod stood in the centre directing traffic Uncle Rod stood in the centre directing traffic Understanding local winds is important Uncle Rod stood in the centre directing traffic. He’d wave an arm: “Light more fires over there!” When the fire crept over the yellow paint boundary, he’d send a group to beat it back. He lay on the ground so he could feel wind flows and predicted from cloud patterns that we could expect a wind change that evening. “When the clouds are low, the wind is more predictable,” he said. “When they’re higher, you have more updraft. It’s important you know your local winds.” The slowly spreading fire was a wonderfully gentle process, which was accompanied by much laughter, chatter and no fear. It’s not generally recognised, but even ‘cultural burnings’, as they’ve become fashionably known in the Landcare movement, are underpinned by a socio/religious aspect.  Women's burning looked after soft soil with herbs and grasses. Women's burning looked after soft soil with herbs and grasses. Fire and culture I asked Uncle Rod what he saw as the cultural essence of Aboriginal-style burning. “Cultural fire is gender-based,” he answered without hesitation. “Man or woman, we had our own secrets. Woman looked after soft soil with herbs and grasses. Men cared for tall trees like stringybarks or ironbarks. Kids had a role crunching up kangaroo dung – it’s key to slow burning along with plants and trees to make charcoal, the magic ingredient for life springing up fresh.”  "a trickle burn cuts through the swathe of old growth at ground level..." "a trickle burn cuts through the swathe of old growth at ground level..." Making Country In reviewing the literature on Indigenous burning, ethno-botanist, Dr Beth Gott found that most historians and researchers believe the major purpose behind lighting up a patch was as an aid to hunting game. In reality, as Traditional Owners frequently assert, it’s to “clean” country – to sweeten and refresh the grass for herbivores; to bare a patch for favoured food species; to remove ‘rubbishy’ dead long grass or tangled shrubs impeding movement. A trickle burn cuts through the swathe of old growth at ground level. It cracks open the soil, releasing dormant seeds, fostering new growth that is fertilised by the slow-cooked charcoal combination of trees, plants and kangaroo dung. “It’s how we make Country,” said Uncle Rod. The patch being burnt was covered in the toxic weed, St John’s Wort. Baring the earth through fire was seen from Uncle Rod’s perspective as a first step in bringing back Country. “This country is wild. We’re getting rid of weeds and retaming it.” Repetitive pattern work is integral to Indigenous design whether in a dot painting, clan symbolism, digging murnong yam daisies or management of land. Fire is no different. Large scale ‘hazard’ burning is antithetical to the Aboriginal approach of building a mosaic pattern, slowly and incrementally, until eventually a whole landscape has been burnt and remade. "Aboriginal mosaic burning patterned the entire continent, as vital, intricate and connected as the scales on a crocodile’s back or the feathers on an eagle’s wing".  Cultural burning in Tasmania as depicted by Joseph Lycett in 1832 Cultural burning in Tasmania as depicted by Joseph Lycett in 1832 Understanding the 'three laws' of Wind, Fire and Rain “We don’t burn the same patch again,” explained Uncle Rod. “We’ll burn next to it. That’s how we build Country.” Pattern work even infuses how people collaborate on the fire ground. Wind, fire and rain – these are the “three laws” that those seeking mastery of fire must understand, said Uncle Rod. Totem groups with interlocking expertise serve each of these three ‘laws’ or elements. Ideally, you would have representatives from all three totem groups present when making fire, said Uncle Rod. “You have [for example] to get waterbird and eagle totems working together.“ The complexities of the clan relationships that underly slow-burn, mosaic pattern work are yet to surface in the mainstream. Our historical perspective of fire in the landscape remains coloured by the ignorant and biased views of most explorers and pioneering settlers towards Indigenous peoples. To his credit, Captain Cook admired 250 years ago what most settlers saw only as threat. Near his namesake town in far north Queensland, he records in his journal sitting on the beach with some sailors while nearby an elder gathered a small group of young men, who, under his instruction, lit a small circle of fire. They were totally at ease and Cook remarks on how the Guueu Yimithirr people “produce fire with great facility, and spread it in a wonderful manner… and we imagined that these fires were intended in some way for the taking of the kangaroo…” But neither he nor those who followed could rise to imagine that Aboriginal mosaic burning patterned the entire continent, as vital, intricate and connected as the scales on a crocodile’s back or the feathers on an eagle’s wing.  A typical CFA burn is lit as a line of fire with drip torches. This method produced a hotter fire and a lot of black smoke. Photo Tracey McRae A typical CFA burn is lit as a line of fire with drip torches. This method produced a hotter fire and a lot of black smoke. Photo Tracey McRae Spreading cultural burning lessons more widely I would contest that we can no longer leave it all to the scientific ‘experts.’ As once occurred with Indigenous people, all of us living in the country ought to be trained in how to use fire and to collaborate with neighbours in cool burning of our forests and vegetation. Declaring war on the bush and burning the bag out of the landscape serves neither man nor beast. We need to replace our overweening fear of fire with a more thorough and nuanced understanding, including how local topography, climate and different vegetation types will affect the fire regimes to be delivered. No doubt some will turn up their nose at the Indigenous affiliations of cultural burning, but wouldn’t it have proven more benign if the explorers and pioneering settlers had paid more attention to the facility with which the locals employed fire?  Courses in Traditional Owner burning are now taught at Cape York. Photo Dale Smithyman Courses in Traditional Owner burning are now taught at Cape York. Photo Dale Smithyman A 'Fire Masters' course for managers of rural landscapes Why don’t we devise a training course in how to deploy fire proactively to prevent conflagrations as well as to optimise our nation’s biodiversity? Such a ‘Fire Masters’ course for forest landholders could be similar in style to the Master TreeGrowers course that has proven so successful in skilling up farm foresters world-wide. It would incorporate the best of both worlds – Indigenous traditional knowledge on mosaic pattern burning combined with the results of evidence-based scientific research on the impact of fire on native flora and fauna in differing ecotypes from heath and savannah through to woodlands and rainforest. Once ignored, Indigenous traditional knowledge has become integrated with the tools and techniques of western science in the widescale burning of the northern savannah across Arnhem Land during the early Dry season. Indigenous ranger programs in northern Australia describe this as the hybrid ’both ways’ approach. We must not, however, as so often happens, take over and speak for Aboriginal people when adapting their traditional expert knowledge of deploying fire. They must lead any cultural burning component and be fully engaged in devising course content. "We must not, however, as so often happens, take over and speak for Aboriginal people when adapting their traditional expert knowledge of deploying fire. They must lead any cultural burning component and be fully engaged in devising course content".  Uncle Rod Mason is the knowledge holder in the south-east of the country Uncle Rod Mason is the knowledge holder in the south-east of the country Monitoring the impact Two issues stand out for serious consideration before making any attempt to roll out cultural burning more widely across the landscape. First, little monitoring has taken place of the impact on native vegetation and wildlife from either cultural burns or CFA/Forest Fire Management cool burns. Anecdotal reports are an unreliable substitute. As a first step, more monitoring of both forms of ‘hazard’ reduction ought to occur as a precursor to implementing any wider landholder training in cultural or cool burning. We need more Traditional Owner teachers with the knowledge A related issue is the lack of knowledgeable cultural burners and who trains more of them and how. Richard McTernan, the co-ordinator with Wooragee Landcare, has worked extensively with Traditional Owners in the south, like Uncle Rod Mason, who hold cultural knowledge of fire. A ceremonial fire man, Uncle Rod now lives in south coast NSW and is considered by his senior men as the knowledge holder in the south-east corner of the country. Richard has focused for much of his life on increasing the use of Indigenous ecological knowledge and assisting the local Aboriginal community in traditional land management. He has taken part in organising some 10 cultural burns. “Burning country is not learnt over night and I believe local knowledge of the environment is essential,” he contends. He goes on to highlight two tricky, entwined questions: who has the right to speak for country and who has proper traditional fire knowledge for that country? The first impinges on often invisible Indigenous protocols and enters the dangerous territory of cultural appropriation. The second relates to ensuring that cultural fire training is both rigorous and relevant to a particular place. Empowering people to burn without proper training may only lead to further devastation of land and wildlife. We will need to tread round these two thorny questions carefully. "Burning country is not learnt overnight and I believe local knowledge of the environment is essential" Richard McTernan  Passionate about his culture, Indigenous man Dean Heta lights up Passionate about his culture, Indigenous man Dean Heta lights up Connecting Aboriginal people back to their cultural identity While ensuring senior Aboriginal knowledge holders remain at the wheel of cultural burning, training of new practicioners could provide another culturally appropriate employment pathway for Aboriginal people. At the Wooragee cultural burn, a young Indigenous man, Dean Heta, spoke passionately about how so many are keen to get back on their land, managing country. “It’s about connecting Aboriginal people back to their cultural identity.” To paraphrase the environmental scientist and polymath, George Seddon: we live here, not somewhere else. After 200 years of searching for land management solutions from other people and places around the planet, it’s time we stopped ignoring the locals and paid attention to what they were doing in the 65,000 years prior to our arrival.  Uncle Rod Mason with Gib Wettenhall Uncle Rod Mason with Gib Wettenhall Guest blogger for February, Gib Wettenhall. Gib Wettenhall has for 25 years written, edited and published books and articles, which acknowledge that the 65,000 year-old Indigenous heritage we have inherited makes Australian landscapes as much cultural as natural. He is the author of The People of Budj Bim, written in collaboration with the Gunditjmara people of south-west Victoria, which in 2011 was Overall Winner of the Victorian Community History Awards. Also, author of The People of Gariwerd, the Grampians’ Aboriginal history, recently reprinted a 3rd time in association with Brambuk. He is currently writing and producing the 3rd in a series of booklets with the Yirralka Rangers, titled Keeping Country, on the bi-cultural approach adopted by this Indigenous land management group in north-east Arnhem Land. As the principal of em PRESS Publishing, his books include Stephen Murphy’s Recreating the Country and Tanya Loo’s nature journal set in the Wombat Forest, Daylesford Nature Diary, which reintroduces a six season Indigenous calendar for the foothill forests. In 2006, he wove the Indigenous heritage of the Gariwerd/Grampians ranges into a series of essays published in a high quality landscape format book with photographs by Alison Pouliot, Gariwerd: Reflecting on the Grampians. He researched and wrote the interpretive signage for the Brambuk National Park and Cultural Centre and is writing the content for interpretive signage for the Budj Bim landscape, which gained World Heritage listing in 2019. Gib can be contacted on [email protected] His publications and past essays can be viewed on www.empresspublishing.com.au

3 Comments

Michelle Francis

24/8/2020 08:40:01 am

Uncle Rod Is not a Ngarigo Elder he is a Walgu and his grandfather is Murray Jack. Uncle Rod also told me when we meet at Charlie Massy’s cool burning in 2016 he still had the blue jacket hid grandfather wore working for the police to track. So please write the truth.

Reply

Steve

24/8/2020 10:44:25 am

Hi Michelle,

Reply

Brent Edwards

19/7/2023 06:32:54 pm

I have spoken to members of my mob tknic (Ngarigo)and we are so interested in further learning more about cultural burning as we are in one of the most volatile places in nsw. I myself am a crew leader for fcnsw and have helped fight out of control fires from the qld border down to the middle of Victoria for more than a couple of decades now. To me it is so obvious that the traditions of the elders be bought back. Could you tell me how we can get training in this so we can have qualified/experienced individuals in this area. My email address is attatched to this comment. Any help would be appreciated thankyou Brent

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed