Recreating the Country blog |

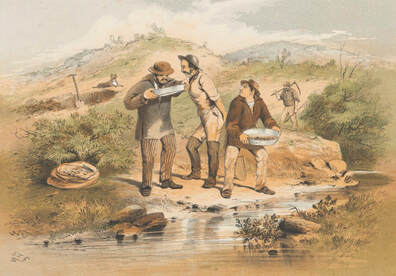

‘Prospectors’ by ST Gill. National Museum Australia ‘Prospectors’ by ST Gill. National Museum Australia The lure of gold dust Since it was first discovered in central Victoria in 185o, gold-dust has played significant part in the modern history of Australia. Thousands of hopefuls arrived on our shores prepared to live rough and make huge personal sacrifices in the hope of finding something yellow and precious. Even small quantities of gold dust would make fossickers jump for joy in paroxysms of pleasure. Though I started my working life as a geologist I could never fathom this obsession with gold. In my early thirties I discovered native plants and realised that the gold dust that excited me wasn't found in stream sediments or deep underground. It's more easily found tantalizingly above the ground in quantities that would fill a gold fossickers bag in no time. It's extraordinarily beautiful and is valued by many more species than just Homo sapiens  Gold-dust Wattle curved seed pods Gold-dust Wattle curved seed pods Gold-dust Wattle, Acacia acinacea Commonly pronounced - Ass-in-ace-y - finishing with a pleasant upward inflection. Its all Greek – acinacea/akinakes = short curved Persian sword or dagger Its name refers to the clusters of remarkable and tightly curved small seed pods that form in early December.  The golden flowers and round leaves of the Gold-dust Wattle. Photo South Australian Seed Conservation Centre The golden flowers and round leaves of the Gold-dust Wattle. Photo South Australian Seed Conservation Centre Some human context This beautiful small shrub produces large bunches of wattle flowers in Spring that are perhaps even more golden than Australia’s floral emblem, described in my previous blog. I’ve seen plants so heavy with flowers that they drooped to the ground under the weight. As an added attraction it has small rounded shiny leaves that give it a soft, delicate appearance throughout the year. This delicate appearance belies its tough drought tolerant character making it suitable for most well drained soils. Like all wattles the Gold-dust Wattle adds nitrogen to the soil which benefits other native plants growing nearby. An ideal plant for the home garden, though notably heavy pruning can make plants sucker, so a light pruning in small gardens may be preferred. Its bushy nature makes it very suitable for mass planting as a low shrub layer in larger biodiversity plantings. For more information on the Gold-dust Wattle click here  Gold-dust Wattle on the roadside between Bannockburn and Teesdale. It's an isolated, inbred small community at risk. Gold-dust Wattle on the roadside between Bannockburn and Teesdale. It's an isolated, inbred small community at risk. Restoring small remnants of Gold-dust Wattle All wattles need large communities of at least 50 plants with diverse genetics to survive for the long term. In some locations the Gold-dust Wattle is in danger of dying out because of low numbers causing lack of plant diversity and inbreeding. For example Gold-dust Wattle grows in the Bannockburn Bush and on the road-side between the towns of Bannockburn and Teesdale. These plant communities lack genetic diversity, are isolated (three kilometers apart) and small. The result of this is they produce very little fertile seed. The germinated seed also shows a lot of variation in vigor, a sure sign of inbreeding. In 2010 the Golden Plains Shire funded the planting of 100 Gold Dust Wattles on the roadside next to the existing remnant community. These plants were grown from seed sourced outside the local area to boost the genetic diversity of this vulnerable plant community. This has lead to an increased production of viable and healthy seed.  Ajax guarding the precious Gold-dust Wattle 'bullion' Ajax guarding the precious Gold-dust Wattle 'bullion' Nature notes The trusses of scented flowers are food for many insects. These flowers are a source of golden pollen and nectar for many native beetles, moths and butterflies. These insects offer a diverse smorgasbord for insect eating birds. The seeds are food for native pigeons, parrots and quail. Ants also gather the seed for its oil rich aril that attaches the small black seed to the pod. Insects also eat the seed frustrating seed collectors when they open the pods to find only brown dust inside. Its bushy form makes it an ideal habit plant for small insect eating birds like the Superb Fairy Wren. Skinks, frogs and small mammals benefit from its low shelter particularly if some logs or rocks are added as part of the landscape design. To read more about small insect eating birds try this excellent ‘Birds in Backyards’ link Collecting seed - harvest time is usually late December to early January  Gold-dust Wattle seed showing the oil rich aril at the top Gold-dust Wattle seed showing the oil rich aril at the top The seed found in healthy plant communities is easy to collect because the pods are usually in clusters. With all wattles, waiting until the pods are opening with some seeds visible makes separating the seeds from the pods much easier. I usually rub handfuls of pods between my gloved hands in a scrubbing motion to detach the seeds. A common garden sieve will aid cleaning by separating the seeds and the pods. Winnowing in a light breeze while pouring the seed from one bucket to another will remove the fine debris leaving the seed clean and ready for storage in a labelled zip-lock bag. Remember to record the name of the species (a short description is good if you're not sure), where it was collected and the date of collection. Other information such as soil type and aspect is very useful when choosing the best home for your seedlings. Propagation Pouring boiled water over the seeds then allowing them to cool is a convenient method. Seeds can then be sown into a seed raising mix or directly into the soil where they are to grow. Cover to a depth more or less equal to the thickness of the seed. They are a bit slower to germinate than other wattles, taking 2 - 4 weeks.

Germinated seed in trays can be planted in tubes as soon as they appear above the potting mix. This is a quick method that minimises the root damage that can occur when transplanting larger seedlings with more developed fragile roots. For more information on propagating wattles go to this link and scroll to the end

3 Comments

Jack

15/9/2020 07:51:51 pm

Thanks for the breakdown - I've been looking for this for some time and recently came across some tube stock. Really excited to get it happening out at Snake Valley - most interesting is what you say about it needing at least fifty in a community. Thanks!

Reply

Steve

16/9/2020 10:38:43 am

Good to hear from your Jack. Yes the acacia genus are a bit like us, needing a large diverse community to survive in the long term.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed