Recreating the Country blog |

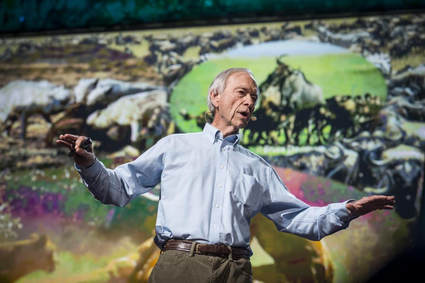

Historically mobs of kangaroos were always on the move Historically mobs of kangaroos were always on the move Historically kangaroo grazing was important for the health of grasslands Grazing is a natural process in the life of a grassland or grassy woodland. Before British settlement mobs of kangaroos would randomly move about their home range and graze on the most succulent grasses and herbs. This chance grazing pattern created patchworks of long and short grass providing different habitats for wildlife. Where the grass was longer in a eucalypt woodland, the nocturnal Rufous Bettong would prosper. In the shorter grassed areas, many of the ground feeding parrot species could feed. Chance grazing was an important part of the grassland ecology and it provided habitats that supported hundreds of native insects and animals and the ecological services they provided.  Overgrazing by 'static' large mobs of kangaroos causes a loss of species diversity Overgrazing by 'static' large mobs of kangaroos causes a loss of species diversity Today there are more kangaroos and fewer grasslands In the twenty-first century kangaroos are still important grazers in our parks and reserves, but two things have changed. There are now more kangaroos and less grasslands for them to graze. These grasslands are also in isolated pockets, forcing kangaroos to spill over onto private land. This allows the mobs to grow well beyond the capacity of the native grassland to support them, putting more pressure on the grassland plants often with disastrous results. This artificial ‘static’ grazing pattern is a radical change from the natural pattern of grazing mobs constantly on the move. A moving mob grazes more generally and doesn’t have time to target the tasty plants. Static grazing allows animals to pick and choose resulting in tasty plants being constantly overgrazed and potentially vanishing.  Mike Robinson-Koss from Otway Greening Nursery inspecting a dense stand of Kangaroo Grass Mike Robinson-Koss from Otway Greening Nursery inspecting a dense stand of Kangaroo Grass Grazing is a species balancer Grazing also helps to ‘open up’ the grasslands. For example when a dominant native grass like Kangaroo Grass, Themeda triandra, is not grazed or burnt for more than ten years, it can become too crowded, choking-out neighbouring herbs and orchids. The Kangaroo Grass eventually declines because of a build-up of dead grass at its base. In contrast, if Kangaroo Grass is grazed or burnt regularly, there are inter-tussock spaces or gaps for other plants to occupy. The Kangaroo Grass is also healthier, each plant potentially living for more than 100 years. The overall result is a stable and diverse grassland plant and animal community.  Grazing Kangaroo Grass. Photo courtesy of Arthur Rylah Institute Grazing Kangaroo Grass. Photo courtesy of Arthur Rylah Institute Grazing can control introduced grasses Aggressive introduced grasses that displace native species in grasslands are difficult to control. Hand weeding is a useful method for small areas but it is labour intensive and creates soil disturbance that encourages more weeds to grow. Spraying with herbicides is expensive, has associated health risks and there are only a few selective chemicals like flupropanate that target problem weeds like Serrated Tussock or Chilean Needle-grass that may be growing in a pristine grassland. Grazing is little used to maintain the health and diversity of grasslands but it has the potential to be a very useful tool. Associate Professor Ian Lunt commented on grazing in The Conversation in 2012; ‘In Tasmania, a number of threatened native plant species survive in grazed areas; if stock are removed the plants are smothered by thick grasses and decline’. Click on this link to read Ian Lunt's complete article; theconversation.com/can-livestock-grazing-benefit-biodiversity-10789  Annual Veldt Grass dominating the westen boundary of Chinamans Lagoon, early spring 2016. Annual Veldt Grass dominating the westen boundary of Chinamans Lagoon, early spring 2016. In Chinamans Lagoon, an 8ha reserve within the township of Teesdale, Victoria, the removal of grazing animals had a profound effect. Two horses and a few sheep had grazed in the reserve for decades suppressing Veldt grasses enough for 55 species of indigenous plants to flourish. In 2002 the grazing animals were removed and this enabled two species of South African Veldt grass, Perrenial, Ehrharta Calycina; and Annual, E. longiflora to spread, eventually swamping the native grassland species within ten years. In 2017 only 8 tree & shrub species and 5 grass species could be found. To read more about identifying and controlling veldt grasses click here;  A flock of Merinos grazing in Chinamans Lagoon. A flock of Merinos grazing in Chinamans Lagoon. Merinos to the rescue In 2016 the wet spring produced exceptional veldt grass growth in Chinamans Lagoon which was a significant fire risk to the Teesdale community. Mowing or brush cutting the long grass wasn’t practical because of the native trees and the ground debris. Research suggested that heavy grazing is the Achilles-heal of Veldt grasses so in September 80 Merino sheep (10 sheep/ha) were introduced over four weeks. This trial was hoping to stress the invading veldt grasses and also open up more inter-tussock spaces for the indigenous grasses to recolonise. The Merinos did an excellent job of reducing the fire risk and preferred eating the exotic veldt grasses and avoided the native spear grasses and wallaby grasses for the first two weeks. The long term plan is to graze the lagoon annually in early spring to weaken the hold of the veldt grasses to allow the native flora to recover. Ian Lunt in another grazing study observed that it took three years for the benefits of grazing became apparent. ianluntecology.com/2011/11/08/restoring-woodland-understories-4/.  Pulse grazing rates will be much higher than the recommended stocking rates for native grasslands of 1-2 sheep/ha Pulse grazing rates will be much higher than the recommended stocking rates for native grasslands of 1-2 sheep/ha Pulse grazing to restore grasslands The ecology of a grassland benefits most from a large mob of kangaroos grazing randomly and then moving on. Pulse grazing with a mob of sheep mimics this pattern of grazing and potentially can be used as a grassland restoration tool. Sheep left to graze for long periods create an even heavily grazed grassy landscape. This may look attractive, but for wildlife it spells loss of habitat and for the grassland it spells loss of biodiversity. Pulse grazing produces an uneven landscape. To achieve this effect a large number of stock are introduced for a very short time. Also called crash/patch/mob grazing, the short grazing time avoids ‘tasty’ plants being targeted and results in more general grazing. In essence the mob is slowly walked through the grassland nibbling as they walk like the kangaroo mobs of old. The number of sheep needed to mimic a mob of kangaroos is likely to be very high. The flock sizes will be much higher than recommended stocking rates. Normally a native grassland would support 1 – 2 sheep/ha if the sheep are left to graze in a paddock for months. Pulse grazing stocking rates over 1 – 2 days, are likely to be 10 – 20 times higher than the recommended rates. For example a 20 ha reserve may require a flock of 200 - 400 sheep.  Monitoring grasslands for change can be a lot simpler than counting plant species in a 1mx1m quadrat each year. Photo points are easy and very useful. Photo Victorian National Parks Association Monitoring grasslands for change can be a lot simpler than counting plant species in a 1mx1m quadrat each year. Photo points are easy and very useful. Photo Victorian National Parks Association Dividing the grassland into small areas with portable electric fencing would enable flocks to be moved daily, producing a desirable patchwork landscape. This would be quite time consuming, but the grazing process would only need to be repeated every 1 – 5 years to keep the grassland healthy. A less time consuming alternative could be found by experimenting with smaller flocks in larger patches over 1 – 2 weeks. To find the right formula some monitoring of the grassland would be necessary. The sheep would be moved when prominent, easy to observe indicator plants were starting to be heavily grazed. Whatever strategy of pulse grazing is adopted, deciding on some management goals like increased species diversity and reduced dominance of certain native grasses is important. Set up photopoints at marked fence posts and in patches containing key species, marked with a hardwood peg, for a valuable aid to recognise change. The plan is to come back each year to the same locations at a similar time and point the camera in the same direction to get the same photo. Comparing the photos over time is a wonderful reminder of where you started and how much the landscape has changed. Below is a set of photopoints that I took in the Teesdale Grassy Woodlands Reserve to monitor Gorse, Ulex europaeus control. Hover over the images for an explanation.  Allan Savory explains how the wondering herds of Wilderbeast kept the vast African grasslands healthy and productive Allan Savory explains how the wondering herds of Wilderbeast kept the vast African grasslands healthy and productive Pulse grazing is working miracles in Africa Ecologist Allan Savory, who is reversing desertification in 15,000,000ha on five continents, promotes ‘Holistic Management and Planned Grazing’ which is very similar to pulse grazing. Savory advocates using huge flocks of sheep or huge herds of cattle. With his grazing system he is turning bare deserts into lush grasslands, but the critical ingredient is that he mimics the constant movement of the wild herds of Wildebeest grazing on the savannahs of Africa. See his TED presentation below, already viewed 4.5 million people, to be inspired with his simple solution to climate change; www.ted.com/talks/allan_savory_how_to_green_the_world_s_deserts_and_reverse_climate_change  Pulse grazing - something to chew on Pulse grazing with large flocks of Merinos mimics the historic grazing pattern of mobs of kangaroos. This should benefit grassland ecologies if it is done when the soil is firm, to avoid compaction caused by hard hooves. Flowering and seed set times will be less important for pulse grazing as many plants will be undamaged in this short grazing cycle. For longer periods of grazing of 1 – 2+ weeks, monitoring grazing will be an important trigger for sheep removal. Flowering and seed set times in spring are times when the sheep should be removed to allow plants to complete their reproductive cycle. To read more on monitoring grazing in native grasslands for conservation click here In Part 5 of the Grassland series guest blogger and respected grassland expert John Delpratt will consider the future of Kangaroo Grasslands in roadside reserves. How they are faring and how we can best look after or restore them To be posted in April

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed