Recreating the Country blog |

|

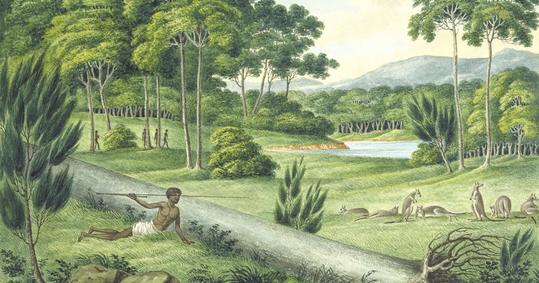

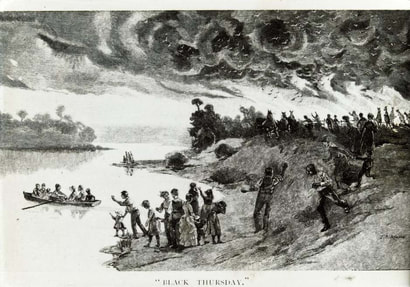

I respectfully acknowledge the traditional custodians of this country past and present. I acknowledge their comprehensive understanding of Australia’s living landscapes. Their culture nurtured this land for over 3,000 generations and used fire as a dynamic management tool. It’s time to listen and learn from the wisdom of Indigenous Elders. It’s time to adopt Traditional Owner burning methods to nurture and to heal the wild landscapes of rural and urban Australia?  A fire stick is often used to start a Traditional Owner burn. A fire stick is often used to start a Traditional Owner burn. ‘Fire Stick Farming’ Anthropologist Rhys Jones changed the way the world thought about Indigenous Australians when he published ‘Fire Stick Farming’ in 1969. He began his article about Aboriginal use of fire with a question. “We imagine that the country seen by the first colonists, before they ring-barked their first tree, was ‘natural.’ But was it? Jones went on to describe a managed Australian landscape that had been changed by burning to produce a land full of wild vegetables and rich hunting grounds. He proposed that fire had many uses to the First Australians and importantly it was used to alter the vegetation. For example to push back forests and replace them with grasslands and grassy forests which were richer in animal and plant foods.  The early explorers found a managed landscape that they compared to an English nobleman's park. Painting J.W Huggins, Swan River 50 miles up 1827 The early explorers found a managed landscape that they compared to an English nobleman's park. Painting J.W Huggins, Swan River 50 miles up 1827 Early explorers observed the effects of indigenous burning In 1848 explorer Major Thomas Mitchell observed ‘fire stick farming’ in New South Wales and suggested it was used to create a comfortable open living environment; “The native applies fire to the grass at certain seasons, in order that a young green crop may subsequently spring up and so attract and enable him to kill or take the kangaroo with nets. In summer, the burning of the long grass also discloses vermin, birds’ nests, etc., on which the females and the children, who chiefly burn the grass, feed. But for this simple process, the Australian woods might have been as thick a jungle, like those of New Zealand or America, instead of open forests”. Explorer Charles Sturt famously described lands around the Murray River in 1830, “In many places the trees are so sparingly (and almost judiciously) distributed as to resemble the park lands attached to a gentleman’s residence in England”. The country that the first explorers described was managed with many small mosaic burns (mostly less than 50ha) that minimised the risk of uncontrolled natural fires. This type of burning conducted every 3 – 4 years produces diverse grasslands and grassy woodlands of varying ages which provides ideal habitat for a diversity of wildlife.  Colonial artist Joseph Lycett in 1820 Van Diemen's Land painted the perfect landscape for hunting kangaroos Colonial artist Joseph Lycett in 1820 Van Diemen's Land painted the perfect landscape for hunting kangaroos Indigenous Australian’s use of fire was sophisticated Bill Gammage in his book ‘The Biggest Estate on Earth’, puts into context what many of the early settlers thought was a natural phenomenon; “In 1788 people shepherded fire around their country, caging, invigorating, locating and smoothing the immense complexity of Australia’s plant and animals into such harmony that few newcomers saw any hint of a momentous achievement”. Gammage contends that Indigenous Australians developed complex patterns of burning that favoured desirable plants and animals. For example, a landscape with belts of well spaced gums next to a wide strip of open grassland and permanent water was perfect for hunting kangaroos. Each native animal has its preferred habitat and a detailed traditional knowledge enabled the first Australians to replicate these habitats with the sophisticated use of fire. By doing this they always had a good supply of root vegetables and plenty of the animals they needed for food, tools and clothing. They also knew in which landscapes to find them.  Black Thursday was one of the largest bushfires to occur in a heavily populated area in Australia’s history. Fifteen people died and 1300 buildings were destroyed. Source - The Guardian Black Thursday was one of the largest bushfires to occur in a heavily populated area in Australia’s history. Fifteen people died and 1300 buildings were destroyed. Source - The Guardian Since 1788 fire has become a constant threat Burning changed after the traditional burning practice progressively stopped in Southern Australia as the white settlers moved in. The fires became unplanned, much hotter and dangerous. This brought about a dramatic change in the type and density of vegetation as the ‘gentleman’s parks’ became dense tangled thickets. On Black Thursday February 6th 1851 a devastating fire burnt nearly a quarter of Victoria. A farmer from the Barrabool Hills near Geelong described the aftermath; ‘It was so awful in its aspect, so sudden in its accomplishment, so lamentable in its consequences, that it can only be equaled in those pages of history where invading armies are described as laying countries waste with fire and sword’ Eventually fuel reduction burns became a necessary and accepted part of rural life. Roadsides were burnt as fire breaks and National Parks and Reserves were regularly burned to reduce the fire risk. But did it? Anecdotal evidence suggests that current burning practices are adding to the overall fuel loads. This is because they are often too hot, too infrequent and the timing is based on a pre-set timetable for fuel reduction. Timetables don’t take into account the unique needs of wildlife, the character of the vegetation, the variable seasons or even the local weather conditions that can change radically without notice. Hot burns result in high rates of germination of fast growing pioneer species like acacias and an increased density of highly flammable fuel within five years. It is still a commonly held belief of people that manage control burns that ‘a hot burn is a clean burn’ and that the fire should be as hot as possible. This type of burn in a grassy woodland can result in an increase in thick understorey and shrub growth that competes with grasslands species. It also kills significant mature trees with hollows. Both of these outcomes are undesirable for the park/reserve and its wildlife, as well as for rural communities.  Ngarigo elder from the Snowy Mountains, Uncle Rod Mason is skilled in the practice of indigenous cool burning. Photo Tracey McRae Ngarigo elder from the Snowy Mountains, Uncle Rod Mason is skilled in the practice of indigenous cool burning. Photo Tracey McRae Indigenous traditional knowledge is alive and well Indigenous elders are now in demand to conduct Traditional Owner burns because of the recognised benefits to the natural environment. For indigenous Australians burning is a spiritual practice that connects them to Country. Burning is also a social occasion even though it is a finely tuned procedure. You can read an account of a recent Traditional Owner burn at Bakers Lane Reserve, Teesdale at this link ancient-australian-culture-cool-burning.html  Traditional Owner burn at Cape York where burning has been practiced for over 60,000 years. Photo Dale Smithyman Traditional Owner burn at Cape York where burning has been practiced for over 60,000 years. Photo Dale Smithyman Traditional Owner (T.O.) burns are very different to modern control burns.

Rhys Jones, respected Australian Anthropologist. 1941 - 2001 Rhys Jones, respected Australian Anthropologist. 1941 - 2001 A fifty year old prophecy I’ll leave the last word on Traditional Owner burning to Anthropologist Rhys Jones who prophetically wrote nearly 50 years ago in ‘Fire Stick Farming’; “Probably for tens of’ thousands of years fires were systematically lit by Aborigines and were an integral part of their economy.… we must do what the Aborigines did and burn at regular intervals under controlled conditions. The days of “fire-stick farming” may not yet be over”. My thanks to Dale Smithyman, an enthusiastic supporter and student of Traditional Owner burning practice, for his guidance with this blog  Traditional Owner burning project at Bakers Lane Reserve, Teesdale, Wiyn murrup yangaramella was driven by the National Landcare Program. Photo Tracey McRae Traditional Owner burning project at Bakers Lane Reserve, Teesdale, Wiyn murrup yangaramella was driven by the National Landcare Program. Photo Tracey McRae A regressive step by the National Landcare Program. Sadly the visionary funding through the National Landcare Program, to employ Indigenous Natural Resource Management Facilitators at the Catchment Management Authorities, will not be offered in the National Landcare Program Phase 2. This decision is extremely disappointing and could be seen as a subtle form of racism that is just as damaging to the re-emergence of a strong indigenous culture as the overt forms of racism that we all despise. It’s time that we question the deep seated and unconscious bias behind a decision like this. It may have been justified with words like ‘restructuring’ and 'cutting costs', but it is a form of racism that is particularly destructive because of it's frequency and because it often goes unnoticed under our radar. If you need a brief escape from reality, 'Seeds the monthly Chronicle' is now into chapter 5. Chapter 6 will be posted very soon. Click here to explore>  This blog describes a Traditional Owner cool burn in detail Ancient Australian culture - the traditional skill of cool burning

10 Comments

20/2/2018 11:17:12 am

Hi Stephen, Great work.

Reply

Steve

22/2/2018 09:57:05 am

Hi Felicity,

Reply

Peter O'Gorman

3/3/2018 11:59:17 am

Dear Steve,

Reply

Steve

5/3/2018 12:48:45 pm

Hi Peter,

Reply

Adrian Brain

23/3/2021 11:19:51 pm

Hello Peter, it's Adrian Brain from Bristol trying to re-establish contact. Old email address still valid.

Reply

13/7/2018 08:26:29 am

I've enjoyed this series a lot, thank you for summarising the frustrations many of us face so succinctly.

Reply

Steve

13/7/2018 05:38:02 pm

Thank you for all those great insights Ben.

Reply

16/7/2018 03:28:40 pm

I'm not sure that all woodlands were kept open by indigenous burning. Box-Ironbark forests and woodlands of Victoria's northern slopes seem to remain fairly open by themself, with very infrequent fires at intervals of 50 years or more. Acacias can indeed germinate in great density after a hot fire, but another hot fire before they set seed can also remove the new growth. Certainly, many temperate grasslands appear to have remained mostly treeless mainly for reasons other than fire. Obviously in some locations fire also was an important element. As you can tell I don't like to agree with generalisations about fire! There is too much (non-indigenous) cultural baggage on both sides of the debate.

Reply

13/8/2018 02:57:25 pm

One of our Members who is a farmer saw on his Australian holiday an indigenous method of "Strip-burning" of grasslands.

Reply

steve

3/9/2018 02:43:22 pm

Hi Bill,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed