Recreating the Country blog |

A beautiful carpet of Common Riceflour, Pimelea humilis, a grassland champion. These plants are still thriving in the Point Richards Reserve, Portarlington A beautiful carpet of Common Riceflour, Pimelea humilis, a grassland champion. These plants are still thriving in the Point Richards Reserve, Portarlington Turning the tide - time for a grasslands revolution You’ve received a mysterious invitation from a close friend to a grassland party. ‘A what? You think – that’s quirky!' When you arrive, you’re greeted at the door by your very excited friend, who ushers you into her lounge where four other women from your preschool group are seated. You give one of them a quizzical look. She raises her shoulders as if to say, ‘search me?' Your friend claps her hands and says excitedly, “Ladies, you’re here to share in my new passion. You’re here to help me turn back the clock 180 years. You’re here to help me plant my grassy back yard into a low maintenance, wildlife friendly, carpet of beautiful, local wildflowers.” Does this gathering of young mums sound feasible to you? Could restoring indigenous grasslands in backyards capture the enthusiastic support of Australians from all walks of life? Is it possible to start a revolution that would see indigenous grassland plants return to the streets and gardens of our nation? The carbon sequestration benefits of planting millions of deep-rooted perennial plants would be reason enough to support a grassland revolution.  Hoary Sunray, Leucochrysum albicans, a grassland champion. It spreads into open areas and isn't grazed by kangaroos or wallabies Hoary Sunray, Leucochrysum albicans, a grassland champion. It spreads into open areas and isn't grazed by kangaroos or wallabies If you're worried about the continuing disappearance of our grassland flora and fauna, you would probably agree that a significant challenge is to develop relatively uncomplicated methods of restoring native grasslands that can be applied on a small or a large scale. This would empower more land managers, including young mums with small backyards, to restore indigenous ecologies on a variety of Australian landscapes. It is an intriguing challenge that desperately needs some serious thought and some practical solutions. What follows in part 3 of Restoring Native Grasslands is a catalyst for discussions about how this restoration could be done. Part 1 of Restoring Native Grasslands, looked at the history of grasslands in Victoria and how our landscapes have changed since settlement in 1835. Part 2 of Restoring Native Grasslands looked at some larger-scale restoration success stories and what can be leant from them.  Bower Spinach, Tetragonia implexicoma, will smother invasive weeds and grow in dry situations under mature trees Bower Spinach, Tetragonia implexicoma, will smother invasive weeds and grow in dry situations under mature trees Grassland plants fight back – in a nutshell; Your mission - to plant an island of grassland plant champions and then get them through their first year.

Native Geranium, Geranium retrorsum, is a forb with a deep succulent root system which competes well with exotic weeds. Native Geranium, Geranium retrorsum, is a forb with a deep succulent root system which competes well with exotic weeds. Blow by blow - in bruising detail: 1. Plant islands of indigenous plant champions. Bellarine Landcare’s Grasslands Interest Group has put together a list of very hardy local grasses, lilies and herbs that are capable of going head-to-head with weedy interlopers. (Thank you also to John Delpratt and Stuart McCallum for your contributions to the list of grassland champions) Grassland Champions list: The Grassland Champion’s list presently includes 76 species, from 50 genera, and 22 families that are found in central Victoria. This list can be extended with other hardy indigenous plants which are local to your area. When the champions begin to take control and improve the soil chemistry, other less hardy plants can be added. The list is in the form of a table that includes other useful information. Click here for the table Always include some nutrient strippers in your plant list. Nutrient stripping plants like Kangaroo Grass will help maintain lower nitrogen (N) & phosphorus (P) levels in your island planting. Plant in groups/clumps of the same species - 10 to 50 plants/clump is ideal. Plant smaller species in larger numbers so they can dominate their given area. See the champions table for the recommended spacing for each species Why plant in same species clumps? Planting in clumps looks great, is nature's way, attracts more pollinating insects and will produce more fertile seed, giving the grassland champions the greatest likelihood of spreading into surrounding areas.  Common Rice Flower, Pimelea humilis (white flowers), surviving on a weedy privately owned building block. The soil fungi needed to support this plant would still be present. Common Rice Flower, Pimelea humilis (white flowers), surviving on a weedy privately owned building block. The soil fungi needed to support this plant would still be present. 2. Choose the best place to plant the champions. Look for helpful indicators of where indigenous plants will best grow. Plant near remnant grassland plants:

Read more about identifying native grasses here Choose the best soil for native plants:

Oxalis comes in many sizes and colours. This yellow flowering variety is probably the most common and invasive Oxalis comes in many sizes and colours. This yellow flowering variety is probably the most common and invasive 3. Avoid planting near invasive weeds like Kikuyu, Couch, Phalaris, Paspalum and Oxalis. These are dominating and destructive perennial weeds that are best managed with an application of herbicide. Ideally follow up with a cool burn when they die and spray with herbicide again if they reshoot. Show them no mercy because they will take over the grassland and destroy all your good works. Once they invade they are much harder to control. Using this process, you will systematically eliminate difficult-to-manage weeds, though it is likely to take two growing seasons. Planting grassland plants before these tough resilient weeds are banished, will only result in disappointment. A note on spraying with glyphosate: Herbicide is a useful tool if it is used safely and intelligently. The time to spray is when the weeds look healthy and are showing strong growth up to 10cm tall. Allow more top growth before spraying deep-rooted weeds like Phalaris and Paspalum. (See pictures below). Kikuyu and Couch grasses die back naturally in winter, so spraying at this time does them no harm. It is better to spray these weeds in late spring or early summer when they are growing strongly. Oxalis is best sprayed at the beginning of its flowering cycle when the plants have just a few flowers. Spraying at this time will kill the many small bulbs (future plants) that are attached to the oxalis roots. My personal story. As an organic vegetable grower, I have tried hand-weeding these difficult weeds year after year. This involved putting the soil through a sieve to remove any potential growing shoots or bulbs which is a slow and tedious process. Yet, still the problem weeds kept coming back. I swallowed my disappointment and applied one well-timed spray with 1% glyphosate, the recommended rate for difficult-to-manage perennial weeds, and eliminated them. To put this spray-rate into perspective; 1% is equivalent to spraying 1 teaspoon of glyphosate concentrate over a 25 square meter area of perennial weeds. The remarkable environmental benefits gained from establishing 5m x 5m of healthy native grassland clearly outweighs my environmental concerns about the use of glyphosate.  Kangaroo Grass mass planted in an island planting to lower nitrogen levels. No nutrient stripping was done on this site, so more hand weeding was required. Kangaroo Grass mass planted in an island planting to lower nitrogen levels. No nutrient stripping was done on this site, so more hand weeding was required. Nutrient stripping – a big blow to the weedy interlopers: Reverse fertilisation.

Burning the stubble when it dries will further lower N & P levels and adds smoke chemicals to the soil that enhance the germination of many native seeds.

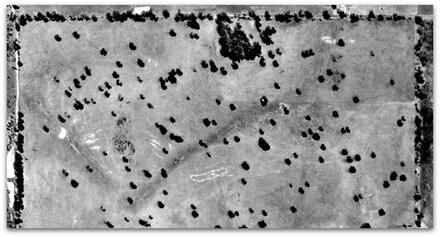

Planting scattered canopy trees will lower soil nitrogen and phosphorus levels. Photo. Deanna Duffy Planting scattered canopy trees will lower soil nitrogen and phosphorus levels. Photo. Deanna Duffy

Planting scattered canopy trees at a similar density to the original pre-settlement spacing will create an open grassy woodland and lower soil nutrient levels. This nutrient lowering effect has been observed to extend at least 1.5 x height of canopy trees from their trunk. Therefore trees reaching a mature height of 20 m will lower soil nutrient levels up to 30 m from the tree’s trunk. Planting nine, 20 m tall canopy trees over one hectare will eventually return the soil nutrients to a pre-settlement lower levels. (This density was calculated on an average spacing of 30 m between canopy trees). Note on planting canopy trees: Canopy trees planted in groups of 5 trees (tree spacing of 3m within these groups) has many advantages:

Planting clumps of shrubs. An alternative design is to include clumps of indigenous shrubs and understorey trees. This will diversify the sources of food and improve habitat for wildlife. To lower soil nutrient levels, the shrub-clumps and the clumps of understorey trees are spaced at 1.5 times their mature height. Therefore, a clump of twenty, 5 m tall shrubs, will lower soil nutrients 7.5 m beyond the outer edge of the clump. A clump of 10 understorey trees with a mature height of 12 m tall, will lower soil nutrients up to 18 m beyond the outside edge of the clump. Within these clumps, the plants are spaced at 2 – 3 m. In this way, a mixed shrubby woodland with grasslands in the open areas could be restored over 1ha of over multiples of 1ha.  Compost teas can be sprayed or watered-in with simple and safe gardening equipment Compost teas can be sprayed or watered-in with simple and safe gardening equipment Making compost teas. Microbe-rich inoculations have been shown to stimulate the revival of some grassland species. Microbe-rich teas can be made from worm-juice, compost or manure. A concentrated tea is made by harvesting worm juice or by placing a permeable bag (e.g. hessian) containing about 9 L (one full bucket = 9 litres) of compost or manure into a 150 L drum of water (40 gallons). (These volumes can be scaled up or down to suit the size of your project). After one week, the microbe-rich water in the drum is diluted to the colour of weak tea and sprayed over the grassland plants. This is best applied when the soil is moist, on a cool, cloudy or rainy day, in mid-spring or mid-autumn. Direct sunlight will kill the microbes in the tea. The benefits of inoculating with microbe-rich teas is discussed in; Restoring native grasslands - part 2  A cool burn will lower soil nutrients and add smoke chemicals which enhance the germination indigenous grassland plants. Photo Gib Wettenhall A cool burn will lower soil nutrients and add smoke chemicals which enhance the germination indigenous grassland plants. Photo Gib Wettenhall Spreading out from the island plantings Paul Gibson-Roy and John Delpratt noticed grassland plants spreading well beyond the edges of their restoration sites; “At all Grassy Groundcover Research Project restorations, native grasses had colonised some tens of metres beyond the boundaries of the original restoration zones and at a large number of sites, forb species had also expanded beyond the restored area” (Paul Gibson-Roy and John Delpratt. 2015. Land of Sweeping Plains. Chapters 11 & 12.). When the island planting is established, the exotic weeds growing around the fringes of the island are your next frontier to conquer. The techniques discussed under ‘Nutrient Stripping’ can be used to expand the island planting:

...the backyard planting

About two years had passed since the grassland party and Cathy was surprised at how well her family had adapted to the new backyard. Instead of a regularly mown grassy patch, it was now a accidental meadow with a mosaic of colour. Her four-year-old loved running through the wildflowers and watching the white and brown butterflies flutter into the air around her. There was something wonderful about seeing a carefree child, arms raised, eyes looking upwards, red curls twinkling in the sun, following the silent random flight of the fluttering butterflies.

5 Comments

John Delpratt

25/1/2023 05:42:43 pm

Another fine contribution to the revolution, thanks Steve. I particularly liked the emphasis on early, effective and on-going weed control. The voice of experience, I suspect. If planting a 'patch' within another vegetation community (e.g. mown exotic grass, aka lawn), perhaps maintain a plant-free boundary of a metre or so wide. This could be a permanent or temporary hard surface (pavers), gravel toppings or a strip maintained with herbicide. This provides an easily-monitored barrier to weed ingress and an area for future expansion of the patch.

Reply

steve

27/1/2023 03:05:59 pm

Thanks John and you're absolutely right about the benefits of providing a barrier to prevent weeds spreading into a newly planted island of grassland plants, particularly if they are aggressive invaders like Kikuyu. A sprayed zone around the island would be a huge benefit to both monitor and control the invasion of these grasses. Do you have a photo of the wildflower meadow planted at Parkville? I would also be interested to read more about how they went about it.

Reply

Fiona Williamson

31/1/2023 12:57:28 pm

Loving this idea for my paddock. BUT it backs onto the creek and that has flooded regularly. The area is clay and usually stays lush over summer. A variety of weeds grow in it though no oxalis (mostly docks and clover and edible weeds, some cape weed). I'm thinking I could spray and solarize over summer. Then pick the No 2 plants off the Where to Plant column in the list that like a wetter, less drained soil

Reply

Steve

3/2/2023 12:38:34 pm

Hi Fiona,

Reply

16/1/2024 03:55:55 pm

hey Stephen, congrats on your excellent Recreating The Country blog. I converted my front yard in Preston from kikuyu and couch grass to a complex of indigenous grasses, forbs and runners in Spring 2022 and many plants are already self seeding (especially windmill grass, ruby saltbush). Kikuyu has all but given up now, just a bit of couch trying to sneak in under fence with neighbours which i hit with glyph occasionally. Brendan

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed