Recreating the Country blog |

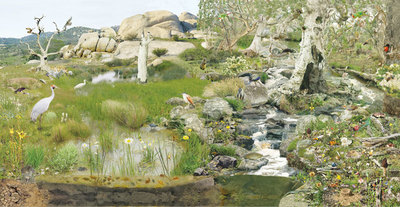

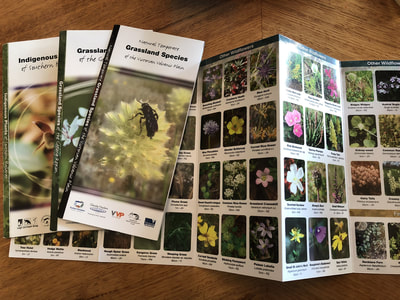

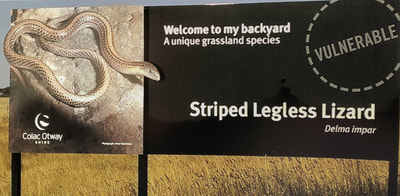

Feeling in the minority? Feeling in the minority? Saving our grasslands and grassy woodlands. If you care, you're in the minority Over the last six months I have looked at how our Australian culture> is limiting our ability to prevent the loss of grasslands & grassy woodlands. I have also suggested some practical solutions such as indigenous burning practice> and strategic grazing>. If you are reading this blog, chances are you have an interest in protecting grasslands. You probably wouldn’t be surprised if I suggest that you and I are in the minority. If I was to put on my ultraconservative hat, I might say to you; “why are we spending buckets of money on saving grasslands”? After all I might add, “money spent on protecting or restoring native flora would have a far greater benefit to the broader community if it was invested in medical research, defence or training more school teachers”. I might conclude that “restoring a kangaroo grassland on a country roadside or a 10 ha bit of scrub on private land benefits very very few Australians”.  Civilisation is underpinned by natural processes and ecological networks Civilisation is underpinned by natural processes and ecological networks Why don't most rational people care? For those of us who are passionate about native flora, these views are confronting and extremely frustrating, but sadly not uncommon. Conservationists scratch their heads with dismay as we wonder why every Australian doesn’t see native flora and fauna as precious. Why don’t most rational people care deeply about the steady slide into extinction of many of our unique plant and animal species? John Delpratt points out the many values of roadside kangaroo grassland reserves in the second of his excellent articles>. Their low fire risk, improved visibility for drivers and their extraordinary beauty. He also mentions the powerful sense of place they provide. But are these tangible reasons that would motivate a nation to protect them? Conservationists are acutely aware of the significant environmental services that natural areas provide. The wealth and health of our whole civilisation is underpinned by natural processes and ecological networks, but to the uninformed these are invisible as is the ongoing loss and destruction  Teesdale Grassy Woodlands isn't very scary but it's a bit messy Teesdale Grassy Woodlands isn't very scary but it's a bit messy Grasslands are messy scary places with hidden dangers! Dr Kathryn Williams is an environmental psychologist who has studied the relationships between people and ecosystems. In ‘Land of Sweeping Plains’ – Managing and restoring the native grasslands of south-eastern Australia (edited by Nicholas Williams, Adrian Marshall and John Morgan), she recalls the raw emotional reaction of a colleague with no previous experience of native grasslands. “Walking through the grassland you can immerse yourself in the novelty and pleasure of such an experience, but it’s one tinged with a visceral anxiety engendered by the possibility of snakes and lurking danger.” Many Australians would nod their heads in appreciation of this experience. They see natural areas as messy scary places that hold hidden dangers.  Neville Oddie with enthusiasts at his Chepstowe property Neville Oddie with enthusiasts at his Chepstowe property Preserving grasslands is old fashioned Williams goes on to describe studies of Australian farmers who consider native grasslands to be less attractive than a paddock of crops or grazing land of introduced grasses. They also considered grasslands to have less ecological value than much smaller areas of remnant woodlands. Well known grassland conservationist and central Victorian farmer, Neville Oddie believes he is viewed by many people as ‘trying to hold onto something from the past that impedes progress today’. This suggests that preserving remnant vegetation is considered by some Australians as old fashioned and in some way holding us back economically. There are certainly some deeply held attitudes in the broader community that are getting in the way of grassland conservation and protection. How then can these old views be brought into the twenty-first century?  A small committed group of volunteers at Teesdale after installing the new interpretive sign. Click on the sign to read more about this project. A small committed group of volunteers at Teesdale after installing the new interpretive sign. Click on the sign to read more about this project. The hard work of a committed few One of the key goals in grassland management is to help people feel connected to grasslands and appreciate their many benefits as well as their fragility. I remember first seeing the Teesdale Grassy Woodlands over twenty five years ago when it was Gorse infested and home to the Teesdale tip. I was with a grasslands expert who became excited about its floral richness after a short walk. This was news to me at the time and it helped me appreciate its values. It started me on a long campaign to save and restore this reserve and through my involvement I developed a strong personal connection. It is now Gorse and tip free, a popular place to walk and highly valued by the Teesdale community because of its natural beauty and uniqueness. This sounds like the happy ending we would all want but it was achieved through the hard work of a small committed group of volunteers. The majority of the Teesdale community were too busy with life’s demands to get involved, attend a wildflower walk or an evening talk on the local birds. Does this story sound familiar? Changing hearts and minds How do we connect the majority of Australians emotionally with wild places? Is it through ‘cues to care’? Aids that reveal the quality and values of messy landscapes? For example;

All of these innovations are gratifying for people with an interest in wild places but sadly they are frequently ‘preaching to the converted’ and have very little impact on the hearts and minds of the broader community. (Hover your mouse over the images below to read the caption and click to enlarge)  Select, connect and protect an Australian animal and plant Select, connect and protect an Australian animal and plant Totem-izing the Australian culture – a wilding revolution To reach the hearts and minds of the average Australian we need cultural and social change as outlined in my recent December> and January> Blogs. Fundamentally we need to adopt many of the values of indigenous Australians and become honorary aborigines as was suggested by Don Burke at the 2016 Landcare conference. This may sound like a radical solution but consider how their culture maintained an ecological balance across this nation for over 60,000 years. A balanced fabric of complex ecologies that has almost been unravelled by our culture and values in less than 200 years. With respect to Aboriginal elders past, present and future I propose that we start in a small way by all choosing a personal plant and animal totem plus an ‘ugly’ (see the brilliant Wilderness Society’s campaign to ‘save Ugly’). Select and connect with an Australian animal and plant species that can be found near your home.  Eastern Yellow Robin, Eopsaltria australis Eastern Yellow Robin, Eopsaltria australis My personal totems could be; The Eastern Yellow Robin is very curious and has a single note song which is usually repeated three times. I chose this species in the hope that they will return to my emerging native garden after an absence of many decades. They are an important habitat indicator species because they need areas with diverse layered vegetation in an area of 5 – 10 ha. An ancient Sweet Bursaria that’s growing in the park next door helped me feel more settled in my new home. Bursaria> are a wonderful small tree that help maintain the ecological balance of woodlands.  White striped freetailed bat, Tadarida australis. photo Museums Victoria White striped freetailed bat, Tadarida australis. photo Museums Victoria The White-striped Free-tailed Bat is one of my favourite ‘ugly’ mammals. In my youth I could hear their high pitched sonar bell like call while they hunted in the upper canopies of trees at night  What are your totems? What are your totems? What are your totems? Become part of a wilding revolution that leads to every Australian choosing their personal totems. Every Australian child could be given a plant and animal totem when they start at preschool. These would become their personal pathway into appreciating our amazing Australian wilderness. Next month I will explore the idea of choosing personal totems and provide some resources to help Please send your ideas so they can be included. Read the heart warming story Amie and the intoxicated kangaroos>

Its based on an actual incident that will amaze you

7 Comments

16/7/2018 03:32:53 pm

Regarding snakes... Too many Australians have an irrational fear of snakes. There are so few actual snake bites, and the vast majority of those are of people who try to handle or kill the snake. Like sharks in the ocean, they are scary to the imagination, not so much in reality. More education on this would be a good thing! Just as sharks don't generally deter us from swimming, snakes shouldn't deter us from walking in the bush.

Reply

Steve

17/7/2018 02:42:05 pm

Thanks Ben,

Reply

John Delpratt

16/7/2018 04:48:21 pm

My own irrational fear is of good words that have 'ise' (or, worse still, 'ize') added to them. Gently putting that aside, it would be a wonderful innovation to allocate a totem to each person entering our education system for the first time. Totems could be drawn from Australia's natural, not necessarily indigenous, environment (e.g. floral, faunal; fungal; geological; geographical). A person's totem could become the basis for a stream of formal, ever deepening and widening inquiry well into primary or, perhaps, early secondary schooling. Late comers (e.g. mature migrants) could be encouraged and resourced to adopt a totem upon arrival. Fully developing and enriching the program may take years, but if contemporary Australia can learn from our first people how to properly live on this continent, we will have plenty of future generations during which we sort out the details.

Reply

Steve

17/7/2018 02:53:38 pm

HI John,

Reply

Gib Wettenhall

6/8/2018 03:44:36 pm

Why stop at totems? We could reinvent songlines relevant to place and integrate with outdoor performances and dances that connected people to nature.

Reply

Steve

20/8/2018 01:07:26 pm

Thanks for that suggestion Gib. Songlines are something that I only have a superficial appreciation of and would love to hear more. I know you have strong connections with indigenous people of the Kimberly region so perhaps you could explain in basic terms how they evolved and how songlines are put into practice today. I hope to hear more.

Reply

KarinP

31/12/2019 02:53:59 pm

I've always loved the willy Wagtail :)

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Click on the image below to discover 'Recreating the Country' the book.

Stephen Murphy is an author, an ecologist and a nurseryman. He has been a designer of natural landscapes for over 30 years. He loves the bush, supports Landcare and is a volunteer helping to conserve local reserves.

He continues to write about ecology, natural history and sustainable biorich landscape design.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed